- Index

- Chronology

- Neighborhoods

- Portfolio

- Ralph Haver

- Commercial

- Customs

- Characteristics

- Family Story

- Jimmie Nunn

- Civic Spaces

- Awards

- James Salter

- Multifamily

- Have a Haver?

An Honest Architect: Jimmie Ray Nunn, FAIA

By Jennifer Gunther

Jimmie Ray Nunn FAIA

Jimmie Ray Nunn FAIA

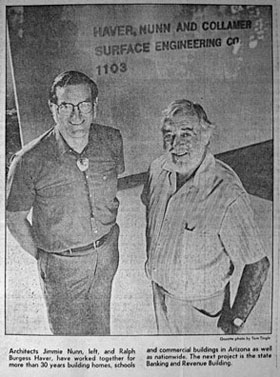

Jimmie Nunn and Ralph Haver worked together for over 30 years

Jimmie Nunn and Ralph Haver worked together for over 30 years

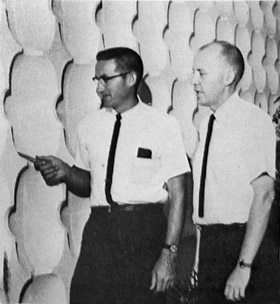

Jimmie Nunn explains the egg crate style cast concrete surface of the Arizona Bank vault (now the Vig Uptown)

Jimmie Nunn explains the egg crate style cast concrete surface of the Arizona Bank vault (now the Vig Uptown)

Nunn at the center of an AIA meeting on professional pricing. Haver on far right.

Nunn at the center of an AIA meeting on professional pricing. Haver on far right.

Precast concrete Y forms were lifted into place to support the waffle roofline of Coronado High School (below)

Precast concrete Y forms were lifted into place to support the waffle roofline of Coronado High School (below)

The precast concrete stadium bleachers at Coronado High were an engineering feat for the region and replicated across Scottsdale schools

The precast concrete stadium bleachers at Coronado High were an engineering feat for the region and replicated across Scottsdale schools

Central Arizona College was one of Nunn's many school assignments

Central Arizona College was one of Nunn's many school assignments

The Hughes helicopter facility where the famous Apache helicopters are tested

The Hughes helicopter facility where the famous Apache helicopters are tested

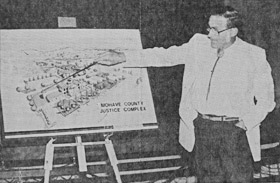

Nunn describes a plan for the Mohave County Justice Complex

Nunn describes a plan for the Mohave County Justice Complex

Kaibab Elementary School in the Arcadia area of Scottsdale

Kaibab Elementary School in the Arcadia area of Scottsdale

The Revlon cosmetics factory was one of many factory projects that fascinated the efficient engineer

The Revlon cosmetics factory was one of many factory projects that fascinated the efficient engineer

The Sunrise Ski Resort Lodge was a project close to Nunn's heart

The Sunrise Ski Resort Lodge was a project close to Nunn's heart

Sunrise Ski Lodge featured gigantic steel scroll chandeliers that were an exclusive design touch on Haver & Nunn's projects

Sunrise Ski Lodge featured gigantic steel scroll chandeliers that were an exclusive design touch on Haver & Nunn's projects

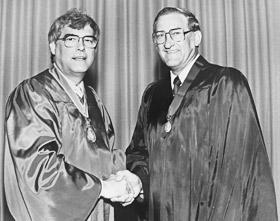

In 1986 Jimmie Ray Nunn received a Fellowship in the AIA

In 1986 Jimmie Ray Nunn received a Fellowship in the AIA

Nunn, Haver, Ed Varney and Fred Guirey were four of the original architects working on Architect's Row in the 50s and 60s. Here they are pictured celebrating on the weekend of Nunn receiving his FAIA.

Nunn, Haver, Ed Varney and Fred Guirey were four of the original architects working on Architect's Row in the 50s and 60s. Here they are pictured celebrating on the weekend of Nunn receiving his FAIA.

Nunn retired in 1985 after 33 years of partnership with Ralph Haver, AIA. He is currently enjoying his retirement in his hometown of Flagstaff, Arizona, living in a sage-green home he built himself. It is situated on a northwest angle and combines the forms of a traditional ranch home and a cabin. Flanked by a deck in the rear, the home has an up-close and personal view of Humphreys Peak, which is part of the Arizona Snowbowl ski area. He curates a ski museum and hits the slopes whenever there’s enough powder, even at the age of 85.

Jimmie Ray Nunn was born on March 18, 1927, in Sweetwater, Texas. When he was 7 years old, his family moved to Flagstaff in hopes of finding employment. Nunn’s father worked for the state highway department in Ash Fork, a city approximately 50 miles west of Flagstaff along Interstate 40. The Nunns later returned to Flagstaff, where the senior Nunn continued his new career until his retirement 60 years later. Coincidentally, Haver & Nunn designed an office building for the Arizona Highway Department in Flagstaff in 1956.

After graduating from Flagstaff High School, where he was a member of the ski team, Nunn joined the Navy as an aviation mechanic. He attended Arizona State College at Flagstaff (now Northern Arizona University) after leaving the Navy in 1946. He transferred to the University of Colorado-Boulder, receiving a degree in architectural engineering upon graduation. He kept busy in the Denver and Durango offices of an architecture firm in Colorado as well as two contracting firms in Flagstaff. Additionally, he worked as a carpenter and a plumber.

“The Denver firm had seven partners,” Nunn said. “They were all ex-military reserve officers, so when we went to war with Korea and Vietnam, they asked if I could stay in Durango to finish what we had going.” He stayed for a few more months to work on several projects, including a school and an ice factory.

Nunn moved to Phoenix in 1952 after being introduced to Haver through a classmate at UC Boulder. The two clicked instantly. “A guy I went to class with was working for Ralph, so I wanted to say hello to this guy,” Nunn recalled of the lunch date that guaranteed his employment for the rest of his career. “I hadn’t even started looking for a job yet. The three of us sat there and had a two-hour lunch of talking. Ralph said, ‘You don’t need to look any further. When can you go to work, Monday morning?’ He had three people and a secretary working for him, and that was about it.”

Monday morning it was. Nunn bought a model home on Palmaire Road in Colson Construction’s Starlite Vista subdivision, which stood on a highly visible corner in a neighborhood that was growing as quickly as the population. He remembered another model home being built after he purchased one of the original two. “I moved in there while they were building more houses — almost all of them have been added on to. I made an addition on the back of mine.” The modestly priced tract homes were designed to expand with the evolving needs of families and budgets, a concept Haver also capitalized on.

Haver’s firm was located on the trendy “Architect’s Row” developing on Camelback Road at Central Avenue. The offices of Fred Guirey, Fred Weaver and Richard Drover, Frank Fazio, Harold Ekman and Ed Varney were also located on the Row. “Phoenix was growing, and there was a lot of business,” Nunn said to describe the design hub. One of his first field assignments was to supervise the construction of housing at Luke Air Force Base that Haver began designing two years prior. Haver’s intention for this major project echoed the objectives of his “Haverhood” tract homes — this time, though, he was designing for GIs instead of the average American.

The base utilized apartment-style lodging before the firm got to work. Haver & Nunn designed and built 725 houses across the street from the base on land that had previously been a cotton field. The designs were typical Haver style, Nunn said, but he noted the roofs had a similar composition to the wooden roof of Haver’s Lou Regester furniture stores. “They had a 6 x 4-inch with a double-tongue roof on the sides, and a V joint on the bottom,” he specified. “They would use spikes to put things together, so you would have random end joints that had to be cut and cleaned to be good. We did a lot of them out there for all ranks, clear down to the officer’s area. The base commander’s house was a single like anyone else’s, but with 5,000 feet total.”

Reflecting the era’s exponential increase in the demand for housing, Nunn hinted at the cookie-cutter element of tract housing that was profitable for developers, but not in tune with many designers’ values.

“When Ralph got into the Haver House that had a lower-pitch roof and a nicer design, there were still other builders putting up homes left and right. We did some houses for Del Webb that were just standard and lousy — you could get them out of a magazine. And yet Webb was a good client of Ralph’s, so he appreciated it,” Nunn said of the firm’s participation in the housing boom. “Most of those houses were red brick. We did quite a bit of work for Webb and other builders too. We did houses in Albuquerque and Denver and subdivisions of 5,000 houses or something. We hardly ever saw them ? all we did was the plans and ship them over,” he said. The sheer amount of houses being built so quickly posed a threat to the personality of each building that was, after all, a family’s home.

Haver would comment on the “indiscriminate growth of tract housing” in the October 1957 issue of Arizona Architect: “The majority of houses today are the product of the merchant builder[, not the designer] … Any improvements on these developments [in mass development and construction] has to come from the combined efforts of the builder, architect, engineer and site planner.” He expressed his strong belief in the necessity of consciousness in design and planning in the commercial activity of real estate development as well. He wrote, “It is a buyer’s market now, and the buyers, becoming more prosperous, are more discriminating. So the successful development has to give more attention to the fact that the potential homebuyers are looking for more than square footage area at a limited price. They are looking for the livability that results from proper planning, good siting, good construction and well-thought-out land planning.” Perhaps outlining his own success, Haver’s central focus on how the family lived in the houses he designed for them was a simple strategy that was frequently overlooked by the industry.

Nunn also pointed out that Haver & Nunn’s military housing was their only housing to be inspected for construction quality, despite their civilian residential buildings greatly outnumbering them. “In those days, there was no supervision. There were no inspectors out there on the side for these kinds of jobs,” he said. “The builders did what they wanted to, and this was the growth of FHA houses. The only ones that we really inspected were military housing, like at Luke Air Force Base.” Nunn would later work on registration boards that brought more order and accountability to the construction and management of these projects.

While Haver continued perfecting his residential designs, which evolved from simple, red-brick houses to open-floor homes with low-pitched roofs and geometric cement block walls, Nunn applied his engineering expertise to a variety of projects that required intensive knowledge and skill that isn’t taught to designers. A pattern began to emerge in Nunn’s repertoire that clearly distinguished his work from that of his partner: he would specialize in planning schools and engineering highly technical jobs for factories and other industrial facilities.

Nunn attended school board meetings to earn the committees’ approval for the firm’s designs. These meetings usually ran late into the night, and the plans were the last item on the agenda. It seemed Nunn got the short end of the stick because Haver detested going to these meetings. “When I left the firm, they almost died because no one wanted to do schools — they really didn’t want to go to the school board meetings,” Nunn said, recalling his long commutes. “For some projects like Phoenix College, I had a better attendance record than some of the board members. I was there at every meeting for something or other.”

Nunn was the master planner for the firm’s major redesign of Phoenix College, originally a WPA project, in 1964. The technicality of the project was what Nunn remembered the most. “We dug up the whole school, built tunnels for chilled and hot water systems and remodeled all the buildings,” he remembered, appearing to envision each system as he listed them off. Gary Nelson, who joined the firm in 1965 after drawing for several firms, drafted the science and music buildings, gymnasium and central plant.

Nelson remembered working with the school administrators as a challenge, but said working with Nunn was another story. Somehow, the role of designer and client had reversed on the project. “One administrator, a former contractor, rewrote our specifications, then took [his own version] to our staff and told them this was their next building,” Nelson remembered of the administration’s incompetence. “We would make comments or critiques on these new designs, and if they were severe enough, he would come back with changes. Once everything was taken care of, he’d make us sign off on the plans, right then and there. His forte was getting stuff done … it was not design by democracy with him.”

On the other hand, Nunn was probably the easiest person he had ever worked for. “He gave me unlimited latitude in what I was doing, whether I was drawing, designing or specifying.” As a draftsperson, Nelson’s key role in redesigning Phoenix College’s buildings was not typical of other firms at the time. Several former employees of the firm recall being given tasks that traditionally were reserved for principals. The design process was a bit more open to collaboration at Haver & Nunn.

Nunn was also the project architect for highly specialized factories and prisons, which require their own set of specific, secure plans. The firm utilized the advances that were being made in architectural design during the ‘70s, using computers to convert the U.S. measurements for its Standard Drywall Products Company factory building to the metric system for a duplicate factory in Europe. What normally took draftspersons hours of redrawing and converting took the computer significantly less time.

“We did a paint factory for the company over in the Bay Area,” he said. “We used their Thoro Seal exterior acrylic coatings on just about every job we did.” The acrylic base of the paint did not shrink or crack like plaster does. “The company decided the plant we built was so good, it wanted us to build the same thing in Belgium. We redid all the plans in metric, but by that time we were all on computers anyway. The computer did it all.”

In 1966, Nunn was the principal architect of the Revlon Cosmetics Factory in Phoenix. Nunn had also made additions to Revlon’s factories in New Jersey. “I worked on that thing for a couple of years, flying back and forth to New York. They had regular concrete floors that were just saturated with wax from the rouges, and they’d be in there steam cleaning and trying to get all this wax and different colors off and everything,” Nunn remembered. He designed a large, computer-operated warehouse that pulled items off massive shelves onto a conveyor belt that went to the shipping department area of the building.

Other Haver & Nunn factories and warehouses in Arizona include the Mardian Construction Co. warehouses on Kunkle Street and Portland Street, respectively (1952), the Ray Lumber Co. warehouse (1961), the American Printing Co. newspaper plant in Glendale (1963), the Del Webb Corp. warehouse and the General Electric offices (1963) and the General Cable Corp.’s rod, mill and wire plant in Kingman (1967).

Nunn was the designer on several projects, including Central Arizona College near Casa Grande. According to Haver & Nunn’s portfolio, the college was designed to provide community space for the area in addition to educational space. It has a Pueblo adobe style and is sited on a hilled desert landscape. Interior designer James Salter’s wrought-iron lamp designs provide attractive detail to the exterior. Flat roofs with parapets and red concrete brick details are other major design features. This school has the designation of being Nunn’s favorite project. “Because I did the whole thing myself,” he said with pride.

Nunn also designed Joseph City High school in northern Arizona. Its sloped roofs set the school apart from Haver’s more square designs. Nunn’s ability to wear multiple hats would come in handy in his push for uniform registration standards and well-defined roles for architects and engineers.

At first featuring only the Haver brand name through the 1950s, the firm was incorporated as Ralph Haver & Associates in 1961. It was rechristened as Haver, Nunn & Jensen in 1963 when Ross Jensen joined the team. Other iterations include Haver, Nunn & Nelson, when Walt Nelson replaced Jensen in the 1970s, and Haver, Nunn & Collamer in the 1980s, when George Collamer came on board. Staffers, however, joked that the firm was simply “Haver, Nunn-the-less.” These two principal architects of the firm adapted their practice to the changing markets of Phoenix: first by designing high-quality, yet affordable housing for Phoenix’s post-war population explosion, then schools and civic buildings and finally industrial projects in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Nunn’s expertise, exposure to emerging technology and travel experience on the many projects of the firm’s diverse portfolio served as a major asset for Haver & Nunn and qualified him to be an administrative leader in multiple architecture organizations.

Like many architects, Nunn is a member of the AIA. “When I moved to Phoenix, there was only the state chapter,” he said. “Soon after, the Phoenix guys wanted to split off from the Tucson guys.” The reason was simple enough: just like today, it was all about the universities. “There was a real rivalry. Boy, if the Board of Regents built a new building at UA and picked a Phoenix architect, then that was worth going to war over. So the two cities split.”

More realistically, the reason for the split was due to logistics and growth. “The meetings for the state chapter were generally in Casa Grande,” Nunn said. “The Tucson architects would go there, and we’d go down on a Saturday morning. Then we finally decided that because both were growing, so we decided to split up.”

In 1957, along with Valley professionals such as ASU Professor James Elmore, architect Richard Drover, Martin Ray Young, Jr., Robert T. Cox and David Sholder, Nunn was a founding member of the Central Arizona AIA chapter to continue the national organization’s mission of connecting architects and other building professionals for excellence, consistency and innovation within the field. Nunn originally served as treasurer, then was secretary the following year. In 1960, he was president of the chapter. Ensuring fair representation and compensation in the specific work assigned to architects and engineers was one of the major issues the design field faced in response to the technological advances made in engineering. An article in the April 1960 issue of Arizona Architect recorded a meeting between John Girand of the American Society of Civil Engineers and Arizona Consulting Engineers Association, president Nunn and Richard Drover and Nicholas Sakellar, chairmen of the committees on collaboration among design professionals. Haver, who was also chairman of the Central AZ AIA’s fee schedule committee, was also present.

In the article Girand said architects and engineers need to better understand who is responsible for the design, which was becoming blurred by engineers’ greater role in the formation of a building. This understanding needed to come from the “grass roots” level of individual architects and engineers, Girand said, which Nunn agreed with.

Speaking from experience, Nunn added that engineers can “have a well-developed sense of the aesthetic” and said they can work with architects to better define project responsibilities. He emphasized that the public needed to better understand the respective work of architects and engineers. “The immediate goal would be to establish better relationships on the local level,” he said.

Nunn’s registration board memberships have also left a lasting impact on architecture in Arizona. “I spent so much time at the AIA and the state board of technical registration (AZBTR), which got me involved in NCARB, the National Council of Architecture Registration Boards. I was the president of the Western region, which comprises 11 western states, including Hawaii and Guam,” Nunn said.

Nunn advocated reciprocity in the licensure examinations that varied among the states, or having uniform content that would transfer easily with professionals across state lines. Of course, Nunn said, some states like Alaska would have special sections on building footings in ice and snow. Overall, his goal was to improve registration standards to ensure quality and safety in design and construction. Before the great demand for buildings, structures went up and burned down as a result of weak or no regulation.

Nunn was awarded the AIA fellowship in 1986 for his service to the profession. “You can get a fellowship in design if you’re a fabulous designer or ‘in service to the profession,’ which for me was all the boards and commissions I worked on for years and years,” he said of the certificate and medal that hangs with numerous other certificates and awards on the wall of his home office. In 1983, he won the Architect’s Medal.

Like Nunn, Haver also served on numerous committees and was a member of many organizations. Both men were admired for their civic service and dedication to improving the Valley’s community. As Nelson put it, though, Haver and Nunn’s personalities were like day and night: “Jimmie didn’t drink, and he was a family man. So was Ralph, but he liked to party.”

Nunn led as vice president of the firm from 1970-1977 and was elected president in 1977.He overlooked Haver & Nunn’s public relations and presented the earnest face of the firm to the community. Friends and family alike agree the two architects perfectly balanced each others’ talents.

Sometimes Nunn mixed business with pleasure, especially when it meant going back to his hometown in northern Arizona. “It seemed like Jimmie was always going somewhere, particularly Flagstaff,” Nelson said. “He drew the entire master plan for the Sunrise Ski Lodge. He even did a rendering of the San Francisco Peaks, completely by himself. It was a very, very nice charcoal and pencil sketch. He walked the entire mountain.”Nunn remembered: “A few buddies and I walked that entire Sunrise area. We rented an airplane, took pictures, and laid out the ski trails from those aerial pictures. Then I went to the EDA and got the money — $29 mill from two different grants. I also had to build a road to the ski area, which is about 12 miles long.”

Sunrise’s buildings range from echoing the classic ranch home design to experimenting with sloped, triangular roofs. There are Salter-designed iron chandeliers in the hotel, which were exclusively used on Haver & Nunn projects. Nunn’s own home has a large Salter chandelier in the living room. Everyone wanted one of these impressive pieces, Nunn claimed.

Nunn met his future wife, Gertrude “Jerry” Schreiber, in 1960 while working as a ski patroller for the winter Olympic Games in Squaw Valley, California. They were married 15 years later. Nunn was a member of the National Ski Patrol System for 33 years. Jerry was inducted into the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame in 2003 for her excellence in ski patrolling and for helping develop the “Avalauncher,” an anti-avalanche gun. She was the first and youngest for many accomplishments, according to a brief biography on the Hall of Fame’s website.

The retired architect briefly served on the Coconino County Planning and Zoning Commission, but health concerns caused him to discontinue his service. Nunn said the city council and county supervisors are where retired architects usually end up, especially when they are friends with the mayor. Nunn’s planning work can be seen on the south campus of Northern Arizona University, specifically in the walkways that are heated in the winter by the hot water pipes that run underneath them. However, a major design update will be implemented throughout the coming years at the university.

Nunn summed up many of his experiences as follows: interesting. “Some of the projects I’ve been involved in are just fantastic,” he said. The straightforwardness of Nunn’s reflection is appropriate because that’s simply what they were for him. There might not be any more honest explanation for an architectural engineer’s activity than that. As the longtime partner of Haver, Nunn & Associates, one of Phoenix’s most prolific firms, he was involved like few others and has left a sizable impact on the lives of thousands of people through his planning and designing. His influence on technical registration and administration continues to guide practice today, and his love for the ski slopes endures.