- Index

- Chronology

- Neighborhoods

- Portfolio

- Ralph Haver

- Commercial

- Customs

- Characteristics

- Family Story

- Jimmie Nunn

- Civic Spaces

- Awards

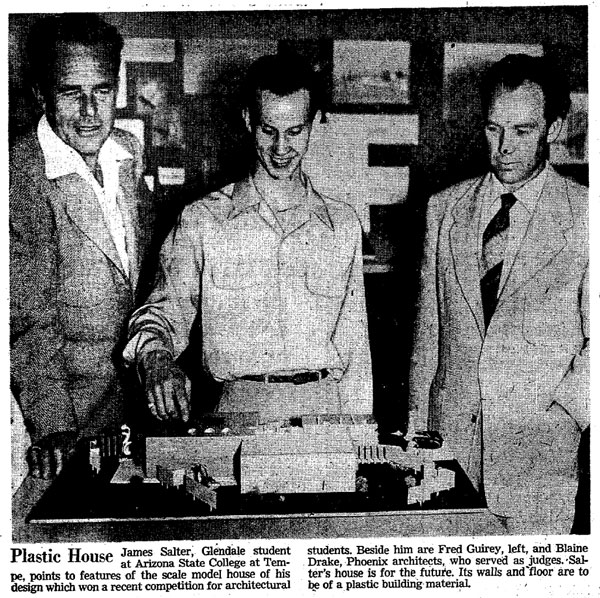

- James Salter

- Multifamily

- Have a Haver?

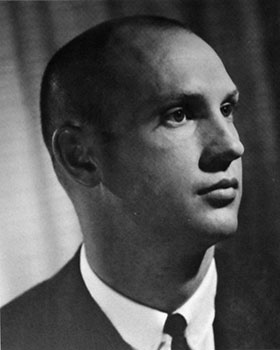

James Lloyd Salter, Associate AIA

Design Director of Haver & Nunn's firm

James Lloyd Salter AIA, Design Director for Haver, Nunn and Jensen

James Lloyd Salter AIA, Design Director for Haver, Nunn and Jensen

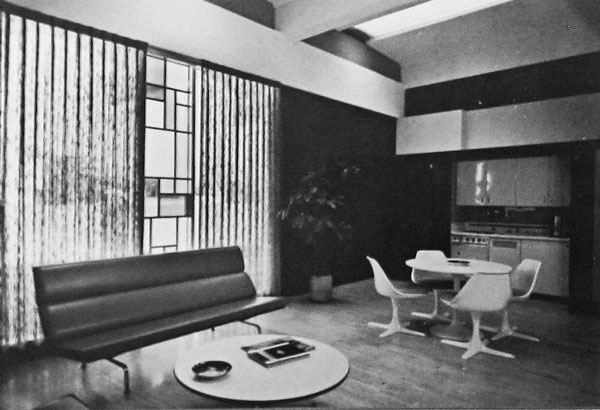

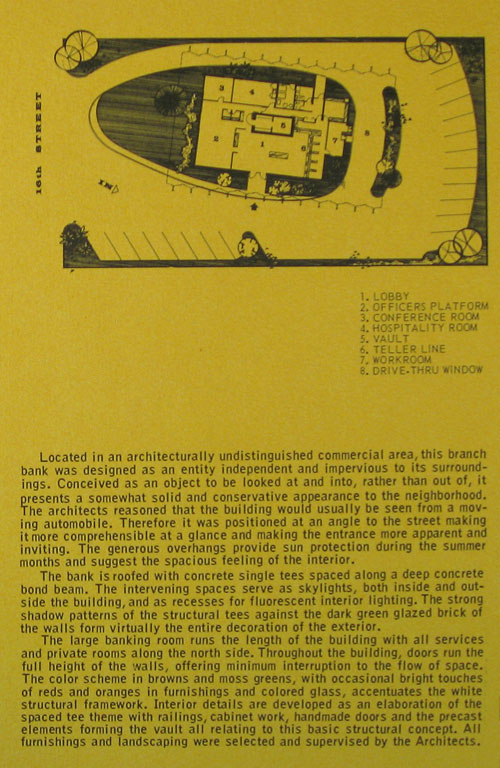

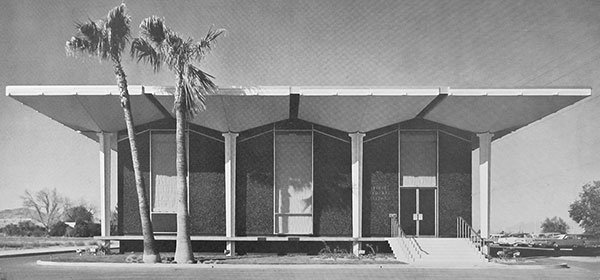

Award-winning interior design for First Federal Savings and Loan in Scottsdale (demolished).

Award-winning interior design for First Federal Savings and Loan in Scottsdale (demolished).

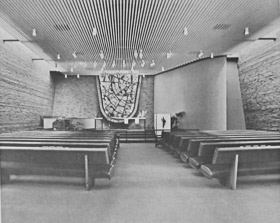

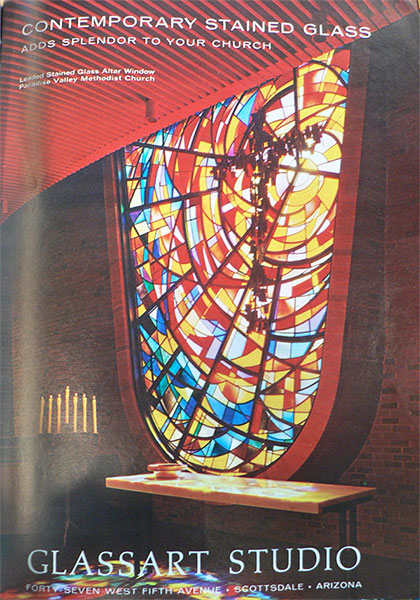

Interior of Paradise Valley United Methodist Church chapel, with custom designed stained glass by Salter, manufactured by Glassart Studio.

Interior of Paradise Valley United Methodist Church chapel, with custom designed stained glass by Salter, manufactured by Glassart Studio.

Curly rolled steel chandelier at Sunrise Ski Resort by James Salter AIA.

Curly rolled steel chandelier at Sunrise Ski Resort by James Salter AIA.

Typical lantern for Dell Trailor condominiums at Avenida Hermosa.

Typical lantern for Dell Trailor condominiums at Avenida Hermosa.

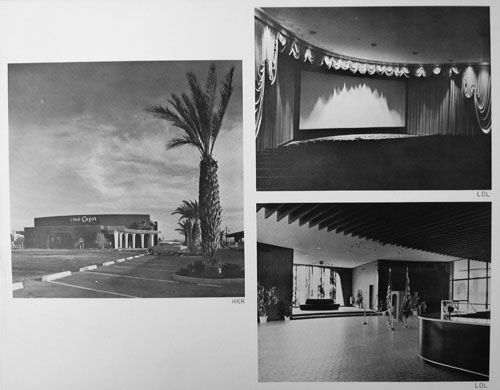

So reads James Salter's official biography in the Haver and Nunn portfolios of the late 1960s. Although the Haver and Nunn names appear on the awards, on the plaques, in the advertisements and newspaper articles, Salter's contribution to the artistry of the firm in the 1960s cannot be understated. Survivors of the firm consistently report that it was Salter's aesthetic that drove the look of many of the Valley's most-loved commercial buildings such as the Kon Tiki, Arizona Bank and the Ciné Capri movie theater. They are all examples of the high glamor and — dare we say it — absolutely fun style that characterized commercial architecture of Phoenix in the 1960s.

Salter was a gregarious and untraditional fellow, and much to the chagrin of his bosses and co-workers, as openly gay as one could reasonably be in the 1960s. The office was generally tolerant of difference, however, and the arts was an entirely appropriate place to be "out". Officemates remember him driving up to work in his red jaguar, dressed in Bermuda shorts, flip flops and sunglasses — designed, like his buildings, to stand out in a crowd. He'd party down at La Casita in South Phoenix long after the last white man had headed back home, and threw legendary bashes at his own Camelback Corridor area home.

Many recall that Salter's behavior often bordered on destructive, but he's remembered most of all for his talent. Salter was a master draftsman and had a real knack for color and materials. It was during Salter's tenure as Design Director that the firm began to rack up recognition for their distinctive style. With his great risk came great reward.

In 1965, Haver and Nunn had enough of Salter's wild ways but thought it best that they not lose some of the firm's best talent, so they made him the head of the Hawaii offices of Haver, Nunn & Jensen to grow their commercial architecture business in The Pacific. They even encouraged him to independently pursue his own specialty in interior design as Salter Harris Company.

It was creative work that Salter seemed to thrive in until one night in 1974, while partying until midnight with some friends at a hotel restaurant, he started doing chin-ups on a lanai railing — a stunt he was infamous for performing. He lost his grip and fell 33 floors to his death at the age of 41.

His passing underscored the end of an era for both the firm and its style, which was soon challenged by the lack of growth in single-family housing, an economic depression, an oil embargo that was brutal to new production, and general changing of public taste in style during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Salter may not have been registered as an architect or had his name on the firm's front door, but this was by choice. He was financially invested as his partners were in the firm's incorporation, and fiercely invested in its success. He likely enjoyed the loose reign to work freely under Haver's casual management style, and because of it, designed some of the most uplifting and well-remembered buildings Arizona has ever seen.

Goldblatt's furniture stores of Chicago hired Haver's firm to conceive of "The World's Largest Ranch House" for their new home center. This concept is probably modeled after the successful scale and plan of Lou Regester furniture store in Phoenix. Even the window treatment with alternating pattern is similar to that previously used at Lou Regester and St. Vincent de Paul.

Goldblatt's furniture stores of Chicago hired Haver's firm to conceive of "The World's Largest Ranch House" for their new home center. This concept is probably modeled after the successful scale and plan of Lou Regester furniture store in Phoenix. Even the window treatment with alternating pattern is similar to that previously used at Lou Regester and St. Vincent de Paul.  Even the employee break room of the Arizona Bank (now The Vig Uptown)

featured stylish furnishings.

Even the employee break room of the Arizona Bank (now The Vig Uptown)

featured stylish furnishings.

First Federal Savings and Loan in Scottsdale won an AIA Chapter Award for Excellence of Design, but it wasn't long before the building was demolished for further development of the Scottsdale Fashion Square area. Most striking was the controversial color of the indigo blue Venetian tile on the exterior — a treatment that people typically either loved or hated. The interior includes Eames furnishings, wood paneling stained green, and two-legged checkbook stands with tapering forms that echo the precast concrete columns holding up the hyperbolic paraboloid ceiling. Beneath the zig-zag roofline is a continuous band of clerestory windows which let in a consistent and natural wash of light without the glare of eye-level windows.

First Federal Savings and Loan in Scottsdale won an AIA Chapter Award for Excellence of Design, but it wasn't long before the building was demolished for further development of the Scottsdale Fashion Square area. Most striking was the controversial color of the indigo blue Venetian tile on the exterior — a treatment that people typically either loved or hated. The interior includes Eames furnishings, wood paneling stained green, and two-legged checkbook stands with tapering forms that echo the precast concrete columns holding up the hyperbolic paraboloid ceiling. Beneath the zig-zag roofline is a continuous band of clerestory windows which let in a consistent and natural wash of light without the glare of eye-level windows.

The Ciné Capri movie theater (demolished) featured a Neo-Neoclassical arcade of precast concrete columns supporting a shade structure with modern frieze design. Survivors of the firm indicate that much of this site's design should be credited to James Salter. The dramatically draped curtain was unlike any other in Phoenix, and its mechanically-orchestrated opening signaled the start of a totally decadent but modern theater experience.

The Ciné Capri movie theater (demolished) featured a Neo-Neoclassical arcade of precast concrete columns supporting a shade structure with modern frieze design. Survivors of the firm indicate that much of this site's design should be credited to James Salter. The dramatically draped curtain was unlike any other in Phoenix, and its mechanically-orchestrated opening signaled the start of a totally decadent but modern theater experience.

The legendary Kon Tiki motor hotel in South Phoenix, according to Jimmie Nunn, was "All Salter." It was demolished during the decline of Van Buren in the 1980s.

The legendary Kon Tiki motor hotel in South Phoenix, according to Jimmie Nunn, was "All Salter." It was demolished during the decline of Van Buren in the 1980s.

Van's furniture store in Honolulu was one of the projects Salter must have been involved with as he ran the Haver, Nunn & Jensen offices in Hawaii.

Most unusual was the inclusion of a three story "Trend Home" model in the store, used for rotating displays of decorator trends.

Van's furniture store in Honolulu was one of the projects Salter must have been involved with as he ran the Haver, Nunn & Jensen offices in Hawaii.

Most unusual was the inclusion of a three story "Trend Home" model in the store, used for rotating displays of decorator trends.Photos copyright 2012 Modern Phoenix LLC