Unboxing Beadle

By Jennifer Gunther

Beadle Archive Research Assistant

Ask any architectural

scholar to name a midcentury architect in Central Arizona and they’re likely to

name Frank Lloyd Wright, with Paolo Soleri listed close behind. But if you ask

a typical modern architectural home-seeker, Al Beadle rockets to the top of the list.

Living

in a Beadle Box marks a high point for those who appreciate the calm order of

his regular grid that must be experienced from the inside out to fully

appreciate. Unlike Soleri and

Wright homes, custom Beadle homes are abundant and much more frequently on the market – and a step up from modern tract housing that was the domain of Haver, Schreiber and dozens of developers solving the problems of the middle class during the postwar boom.

Nobody knows better

than the Beadle family what life is like inside classic Beadle Architecture. In

the span of nearly 40 years, Nancy Beadle lived in several custom homes

designed by her husband, Desert Modernist Alfred “Al” Beadle (1927-1998), where

they raised five children. Few have been closer to Modern architecture than she has.

Now in her late

eighties, Nancy has spearheaded the effort to preserve her husband’s creative

legacy as midcentury modern architecture approaches the traditional age criterion

for historic preservation. She has identified over 100 of Al’s residential

structures and nearly 100 commercial buildings since his passing with her

family and Al’s former associates by her side. In partnership with Modern

Phoenix she has helped expand documentation of Al’s work to include digital-format

source material and a master database.

Ask any architectural

scholar to name a midcentury architect in Central Arizona and they’re likely to

name Frank Lloyd Wright, with Paolo Soleri listed close behind. But if you ask

a typical modern architectural home-seeker, Al Beadle rockets to the top of the list.

Living

in a Beadle Box marks a high point for those who appreciate the calm order of

his regular grid that must be experienced from the inside out to fully

appreciate. Unlike Soleri and

Wright homes, custom Beadle homes are abundant and much more frequently on the market – and a step up from modern tract housing that was the domain of Haver, Schreiber and dozens of developers solving the problems of the middle class during the postwar boom.

Nobody knows better

than the Beadle family what life is like inside classic Beadle Architecture. In

the span of nearly 40 years, Nancy Beadle lived in several custom homes

designed by her husband, Desert Modernist Alfred “Al” Beadle (1927-1998), where

they raised five children. Few have been closer to Modern architecture than she has.

Now in her late

eighties, Nancy has spearheaded the effort to preserve her husband’s creative

legacy as midcentury modern architecture approaches the traditional age criterion

for historic preservation. She has identified over 100 of Al’s residential

structures and nearly 100 commercial buildings since his passing with her

family and Al’s former associates by her side. In partnership with Modern

Phoenix she has helped expand documentation of Al’s work to include digital-format

source material and a master database.

Until recently,

primary sources on Al’s architecture were largely limited to Nancy’s personal

collection, collections of associates Wayne Chaney and Ned Sawyer and the

private, mostly paper archive in The Design School

library at Arizona State University.

Once prone to the faults of oral tradition,

the locations of each building are now carefully pinned, and the map of

commercial structures is freely available. Travelers from as far away as France

have used the map and the Beadle Archive to study and explore architecture in

Phoenix.

Beyond giving us a

greater perspective of her husband’s unusual approach to architecture, Nancy’s stories

as primary user of the Beadle Houses shed light on the places women have occupied

in the history of Modernism, a subject feminist scholars have taken on as more

women enter the profession.

Though Nancy speaks tenderly of her close

relationship with an architect often described as gruff, she stops

short of identifying herself as his muse or even his client. We see

her not just as a glorified secretary or bookkeeper but as a partner who often wrote

project specifications and to this day promotes his work though tours and

educational events. There is no better ambassador of the brand known as Beadle

Architecture.

Until recently,

primary sources on Al’s architecture were largely limited to Nancy’s personal

collection, collections of associates Wayne Chaney and Ned Sawyer and the

private, mostly paper archive in The Design School

library at Arizona State University.

Once prone to the faults of oral tradition,

the locations of each building are now carefully pinned, and the map of

commercial structures is freely available. Travelers from as far away as France

have used the map and the Beadle Archive to study and explore architecture in

Phoenix.

Beyond giving us a

greater perspective of her husband’s unusual approach to architecture, Nancy’s stories

as primary user of the Beadle Houses shed light on the places women have occupied

in the history of Modernism, a subject feminist scholars have taken on as more

women enter the profession.

Though Nancy speaks tenderly of her close

relationship with an architect often described as gruff, she stops

short of identifying herself as his muse or even his client. We see

her not just as a glorified secretary or bookkeeper but as a partner who often wrote

project specifications and to this day promotes his work though tours and

educational events. There is no better ambassador of the brand known as Beadle

Architecture.

As wife, mother and

homemaker Nancy performed her role in houses whose dramatic expression of

Modernist design principles set them apart from the era’s American Dream houses.

Typical midcentury ranch homes in Phoenix were mass produced on large tracts with little variation in their materials or rooflines to project

an enduring image of domestic tranquility and social order. In contrast, the Beadle

Houses are sited on uniquely shaped tracts, often nudging right up to

undisturbed desert nature. Flat rooflines, large plate windows and smooth, boxy

façades express “elegance carried out to an extreme,” Al’s definition of

simplicity.

The typical home developer sought to create cozy spaces for as many

nuclear families as possible. The character and value of Beadle Boxes immediately

come in to perspective once they are approached and entered.

As wife, mother and

homemaker Nancy performed her role in houses whose dramatic expression of

Modernist design principles set them apart from the era’s American Dream houses.

Typical midcentury ranch homes in Phoenix were mass produced on large tracts with little variation in their materials or rooflines to project

an enduring image of domestic tranquility and social order. In contrast, the Beadle

Houses are sited on uniquely shaped tracts, often nudging right up to

undisturbed desert nature. Flat rooflines, large plate windows and smooth, boxy

façades express “elegance carried out to an extreme,” Al’s definition of

simplicity.

The typical home developer sought to create cozy spaces for as many

nuclear families as possible. The character and value of Beadle Boxes immediately

come in to perspective once they are approached and entered.

Squaring up a practice

Nancy says it all started as a love affair. The year was 1948, and the couple had just married in their home state of Minnesota. The newlyweds briefly rented a home while Al, who had recently returned from service in the Navy Seabees and had virtually no academic training in architecture, went back to work in his father’s commercial kitchen contracting business as a drafter and construction assistant. In 1950 he purchased property from a builder to construct the first Beadle House in Minnetonka, about a year after the couple’s first child, Steve, was born. “Al told the builder that

he wanted to do it by himself,” Nancy says. “We made the decision together ─ it was simply part of our love. I always felt he would take care of me.”

Legend goes that no

bank at the time would give a business loan to Al because he wasn’t licensed or

connected to a firm. A 2013 Phoenix Magazine article on the family suggests Al

secured financing by promising he would include his office on the home site, a

maneuver that let him provide for his growing family and further hone his

creative process.

Nancy was not

eligible for her own home loan because of her sex, which only adds weight to

her sentiment that her husband would take care of her. Some readers will be

surprised to learn it wasn’t until the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 passed that women could take out a loan in their own name.

Al built another

house in Minnetonka before the young family packed up for Phoenix in 1951. He sold

Beadle House 2 to a friend to pursue the opportunity to move forward by

designing commercial kitchens for his father’s business, Beadle of Arizona.

“Al told the builder that

he wanted to do it by himself,” Nancy says. “We made the decision together ─ it was simply part of our love. I always felt he would take care of me.”

Legend goes that no

bank at the time would give a business loan to Al because he wasn’t licensed or

connected to a firm. A 2013 Phoenix Magazine article on the family suggests Al

secured financing by promising he would include his office on the home site, a

maneuver that let him provide for his growing family and further hone his

creative process.

Nancy was not

eligible for her own home loan because of her sex, which only adds weight to

her sentiment that her husband would take care of her. Some readers will be

surprised to learn it wasn’t until the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 passed that women could take out a loan in their own name.

Al built another

house in Minnetonka before the young family packed up for Phoenix in 1951. He sold

Beadle House 2 to a friend to pursue the opportunity to move forward by

designing commercial kitchens for his father’s business, Beadle of Arizona.

“Phoenix was a

different landscape, that’s for sure,“ Nancy says, understating the big change.

Beadle House 3 was built that same year on Northern Avenue, the bleeding edge

of civilization in Phoenix, where Al commuted to his father’s headquarters at 10th

Avenue and Jefferson. He built Beadle House 4 on Royal Palm Road months later,

which features a unique shelving system highlighting the raked-joint brick he

used as the main wall material. Beadle House 5 went up the following year,

located right down the street from its predecessor.

As Al’s portfolio of

residential projects grew, so did his family. Nancy gave birth to daughter

Nansi Le in 1953.

“Phoenix was a

different landscape, that’s for sure,“ Nancy says, understating the big change.

Beadle House 3 was built that same year on Northern Avenue, the bleeding edge

of civilization in Phoenix, where Al commuted to his father’s headquarters at 10th

Avenue and Jefferson. He built Beadle House 4 on Royal Palm Road months later,

which features a unique shelving system highlighting the raked-joint brick he

used as the main wall material. Beadle House 5 went up the following year,

located right down the street from its predecessor.

As Al’s portfolio of

residential projects grew, so did his family. Nancy gave birth to daughter

Nansi Le in 1953.Boxes to frame lives, not photos

“The fact of the matter was my marriage to a Modern architect simply necessitated all the moves,” Nancy says. She finds it funny that Al would pick out the furniture, sparing her from being the diminutive “interior decorator” of a more sexist past. He designed several clients’ interiors as well. “Al had three sisters, and they used to say to me, ‘Why aren’t you picking out your furniture or the colors for your house?’ I would say ‘That’s Al’s job. I just clean it.’ They’d laugh and say I was crazy,” she remembers. “I know a lot of women did that, but I didn’t want to. I thought he knew better than I did what worked for his design.” Photo: Arizona Republic

Nancy clarifies she

never felt dismissed by her husband. Though they would combine ideas from time

to time, she judged that Al’s concentration on site, material and program was so

intense he wouldn’t often venture outside of his own headspace. Constructions,

the most definitive source on his architecture, offers the perspective that Al

arranged bathroom tiles so precisely that none of them needed custom cutting to

fit to plan. Al was not unlike other architects who wouldn’t see eye to eye

with clients, or perhaps more accurately would not compromise his own vision

for their more limited view.

Daughter Gerri, born

in 1960, remembers the family homes were clean and easy to maintain. It can’t

be overlooked that “women’s work” became slightly less physically demanding as

a direct result of Modernist preferences for minimalism and less fussy

materials like glass, mica and stainless steel.

“My dad was a firm

believer in lots and lots of closets because you could hide all your stuff in

there,” she says, alluding to the once-prevailing notion that everything and

everyone in the home had its proper place.

Nancy took care of

the children with periodic help from a housekeeper named Vera as well as her

own mother, who lived in the Triad Apartments Al designed in 1964 as a Case

Study House.

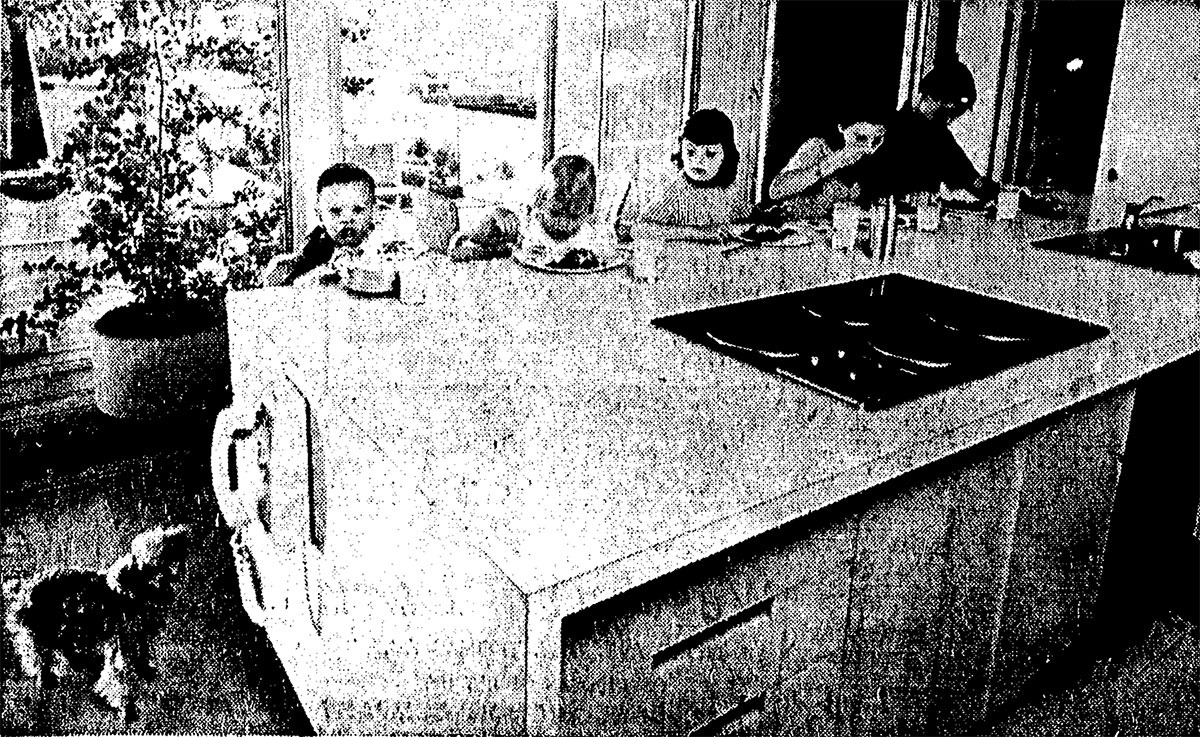

One of Al’s greatest

pleasures as an architect was bringing people together. This was especially

visible in the kitchen, the quintessential space where midcentury women

nurtured their families. In marked contrast to the habit of confining women to their

primary place of work, where cooking, dish washing, scrubbing and even laundry

were completed daily without pay or recognition, Gerri notes that no one in the

open kitchens her father designed would miss out on the party while they

prepared hors d’oeuvres.

“Hosting

sophisticated cocktail parties was only natural for us in that house,” Caren says, remembering her mother’s gorgeous collection of

formal dresses.

She says Nancy would

sometimes have to hide them in order to keep Al from swapping them out for newer,

even more beautiful gowns. “He liked to see me in new clothes,” Nancy remembers.

“We had a bit of the good life.”

When asked if Al’s

all-black uniform made laundry easier, she smiles.

Photo: Arizona Republic

Nancy clarifies she

never felt dismissed by her husband. Though they would combine ideas from time

to time, she judged that Al’s concentration on site, material and program was so

intense he wouldn’t often venture outside of his own headspace. Constructions,

the most definitive source on his architecture, offers the perspective that Al

arranged bathroom tiles so precisely that none of them needed custom cutting to

fit to plan. Al was not unlike other architects who wouldn’t see eye to eye

with clients, or perhaps more accurately would not compromise his own vision

for their more limited view.

Daughter Gerri, born

in 1960, remembers the family homes were clean and easy to maintain. It can’t

be overlooked that “women’s work” became slightly less physically demanding as

a direct result of Modernist preferences for minimalism and less fussy

materials like glass, mica and stainless steel.

“My dad was a firm

believer in lots and lots of closets because you could hide all your stuff in

there,” she says, alluding to the once-prevailing notion that everything and

everyone in the home had its proper place.

Nancy took care of

the children with periodic help from a housekeeper named Vera as well as her

own mother, who lived in the Triad Apartments Al designed in 1964 as a Case

Study House.

One of Al’s greatest

pleasures as an architect was bringing people together. This was especially

visible in the kitchen, the quintessential space where midcentury women

nurtured their families. In marked contrast to the habit of confining women to their

primary place of work, where cooking, dish washing, scrubbing and even laundry

were completed daily without pay or recognition, Gerri notes that no one in the

open kitchens her father designed would miss out on the party while they

prepared hors d’oeuvres.

“Hosting

sophisticated cocktail parties was only natural for us in that house,” Caren says, remembering her mother’s gorgeous collection of

formal dresses.

She says Nancy would

sometimes have to hide them in order to keep Al from swapping them out for newer,

even more beautiful gowns. “He liked to see me in new clothes,” Nancy remembers.

“We had a bit of the good life.”

When asked if Al’s

all-black uniform made laundry easier, she smiles.

Photo: Arizona Republic

1963 is considered to

be Al’s most prolific year, during which he built Three Fountains and The

Boardwalk apartments, and the Executive Towers. Acclaim from local and

even national media poured in. Nancy supported her husband’s success by hosting

Modern home tours, an informal but effective way of promoting his work.

“I remember this one real estate agent

who would drive around Phoenix and point out the different styles of houses,”

Gerri says. “Tudor, ranch, Beadle. She thought Beadle was an architectural

style!”

Photo: Arizona Republic

1963 is considered to

be Al’s most prolific year, during which he built Three Fountains and The

Boardwalk apartments, and the Executive Towers. Acclaim from local and

even national media poured in. Nancy supported her husband’s success by hosting

Modern home tours, an informal but effective way of promoting his work.

“I remember this one real estate agent

who would drive around Phoenix and point out the different styles of houses,”

Gerri says. “Tudor, ranch, Beadle. She thought Beadle was an architectural

style!”

Photo: Ernest A. and Billie W. Uhlmann Family Archive

Photo: Ernest A. and Billie W. Uhlmann Family Archive

Beadle House 12: The family’s favorite

The architecture of the Beadle Houses uniquely permeated Nancy and Al’s relationship and family life. The inclusive program of Beadle House 12 on Oregon Avenue (1966) stands out in Nancy’s memory as her most beloved home. “The kids really grew up there,” she says. Steve, Nansi Le, Caren, Gerri and Scott, who was born in 1962, were staggered through different stages of childhood and adolescence, and often took care of each other. Number 12 is the only Beadle House that was not built by Al from the ground up: a California architect named Edward Killingsworth, FAIA built it. Al renovated it to feature floor to ceiling windows to bring the outdoors in. He later split the lot to transform a guest house into his studio. A pit in the living room held a baby grand piano that Al loved to play by ear, and the Olympic swimming pool outside was a fixture for family fun. “It was a different time,” Gerri says. “There was no gate around the pool, not even a fence around the property.” The dramatic windows let Nancy keep an eye on the kids from the kitchen, a midcentury woman’s workspace. With Al’s studio just a walk across the yard, both parents were present to give their children plenty of attention and affection. Caren, born in 1957, remembers associates coming and going. Ned Sawyer, a close family friend who lived at The Boardwalk, was always over. “As a little kid it was nice, but as we got a little older it was a bit difficult,” Gerri says about her parents’ constant presence. “If you didn’t get home from school right away, you wouldn’t hear the end of it from Mom or Dad.” Outside of her family life, Nancy, better known as Mrs. Alfred Beadle, was involved in local groups like the Women’s Architectural League. A 1971 Arizona Republic article notes she helped the League organize a glamorous Beaux Arts Ball and tour of the Phoenix Art Museum, whose proceeds went to constructing a “Mini Park” in Phoenix. The family would hop

in one of Al’s luxury cars to dine at The Flame steakhouse on Adams Street

downtown, one of the many restaurants that Beadle designed but which has long

since been demolished. Baskin Robbins on Camelback was another favorite. Daily

meals were eaten together at the round kitchen table, though the parents ate at

the kitchen bar.

As Nancy says, that’s

all there was to it: The designer inhabited his own spaces with his family and

even did the dishes on occasion. She loved every minute of it.

The family would hop

in one of Al’s luxury cars to dine at The Flame steakhouse on Adams Street

downtown, one of the many restaurants that Beadle designed but which has long

since been demolished. Baskin Robbins on Camelback was another favorite. Daily

meals were eaten together at the round kitchen table, though the parents ate at

the kitchen bar.

As Nancy says, that’s

all there was to it: The designer inhabited his own spaces with his family and

even did the dishes on occasion. She loved every minute of it.

Photo: Arizona Republic

Photo: Arizona Republic

Building a legacy

It’s important to note the Beadles also experienced lows together — the Phoenix chapter of the American Institute of Architects’ suit against Al for practicing without a license was chief among them. An economic slump in the 1970s hit many firms hard and took its toll on Al’s practice, sometimes reducing his workload to one residential project per year. Gerri thinks this might be why none of Al’s children followed in his footsteps. Caren says Al didn’t view his family or his career as means to fame. “It was about doing what he loved to do and the art,” she reflects. “He wanted what was going to make us the happiest, not what he wanted us to be. I personally think my father was a very modest man who didn’t necessarily want the attention to be on him.” Nancy has been deeply involved in efforts to share the significance of her husband’s architecture with Phoenix property owners, developers, civic leaders and cultural advocates for nearly two decades. She lived in the Executive Towers for several years after Al passed in 1998. “Being there with his design really comforted me,” she says. “Sometimes it’s hard knowing he’s gone.” She now lives with daughter Gerri in north Phoenix. In 2013 Nancy hosted part of the Modern Phoenix tour of Arcadia, sharing the backstory of Beadle House 6, aka White Gates, with hundreds of eager design enthusiasts. A stroke in 2014 hardly held her mission back. In 2015 she partnered with Modern Phoenix to launch a special registry for Beadle homeowners, who can sign up to receive a commemorative steel plaque bearing Al’s signature. Homeowners have joined in on an informal conversation to learn more about preserving their Beadle homes. They gather in person and on social media to swap stories and restoration ideas. Nancy’s love affair continues, and with her recent push to preserve Al’s work she’s been inviting everyone to enjoy the passion, too.

Bibliography

Interviews with Nancy, Caren and Gerri Beadle, June and July 2015.Dolores Hayden, “From the Ideal City to Dream House” in Redesigning the American Dream: The future of housing, work and family life (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2002), pp. 33-52.

Dolores Hayden, “Nurturing, home, Mom and apple pie,” in Redesigning the American Dream: The future of housing, work and family life (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2002), pp. 81-118.

Joan Ockman, “Mirror Images: Technology, consumption and representation of gender in American architecture since World War II” in The Sex of Architecture, eds. Diana Argest, Patricia Conway and Leslise Kanes Weisman, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1996), pp.191-210.

Alice T. Friedman, “Not a muse: The client’s role at the Rietveld Schröder House” in The Sex of Architecture, eds. Diana Argest, Patricia Conway and Leslise Kanes Weisman, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1996), pp.217-232..

Mark Lamster, “A personal stamp on the skyline,” New York Times, April 3, 2013, accessed June 2015.

Dawson Fearnow, “Beadle Mania: The secretly stable life of the Valley’s most outrageous architect,” Phoenix Magazine, December (2013): pp. 90-95.

Sue Kern-Fleischer, “Al & Nancy Beadle: Architecting a life of love,” ImagesAZ, January (2015): pp. 50-55.

Mary and Russel Wright, Guide to easier Living (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2003).

Bernard Michael Boyle, Constructions: Buildings in Arizona by Alfred Newman Beadle, (Cave Creek, Ariz: Gnosis, Ltd., 2008).

“Beaux Arts Ball Set for Saturday,” The Arizona Republic, February 3, 1971, E-5. Photos ©2015 Modern Phoenix LLC, Arizona Republic, Shelor Family

or used with kind permission of Beadle Architecture/The Estate of Al Beadle