Marion Estates Neighborhood

- History

- Homes 1

- Homes 2

- Cool Home

- New + Renos

- Favorite Pix

- 2018 Tour

- Evertson

- House of Light

- Landscape

House of Light: A Glowing Promise Fades to Dying Ember

Ard Hoyt's Gold Medallion All-Electric Homes in Marion Estates By Tazmine Loomans

When the housing boom was gaining traction in the 1950s, generating electricity wasn’t as efficient as it is today. To streamline production and meet increasing demand, the utility providers rushed to build more power plants, the vast majority of which were coal-fired. As electrical plants were able to produce more power, homeowners were encouraged to consume more of it; the more they used, the less they paid.

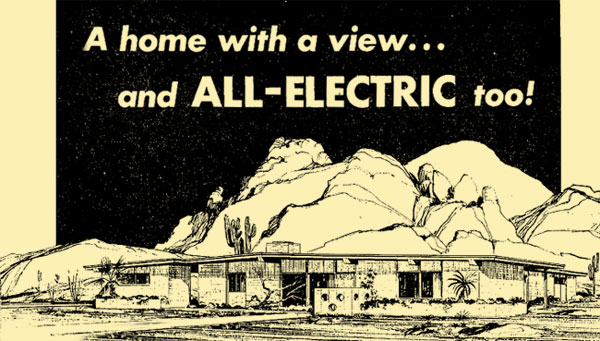

Vintage illustration from The Arizona Republic advertising Ard Hoyt's House of Light

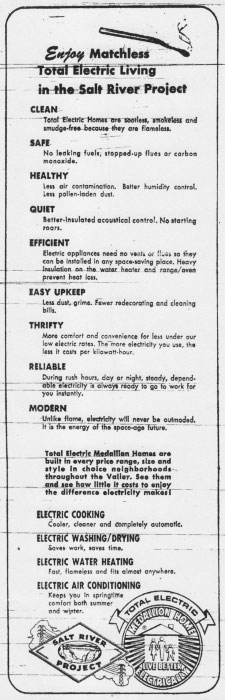

Electricity can’t be stored for future use. It has to be delivered right when it is generated. It was in the best interest of the electric industry (led by the Edison Electric Institute and General Electric) that people consume as much electricity as possible to make the best use of the expensive equipment that was required to generate power for peak demand. It’s similar to the idea that the airline companies would prefer to have their planes full to help cover operational expenses. Today, electric utilities are mandated by government and other entities to reduce the amount of electricity they generate through traditional coal-fired power plants, but in the 1950’s these mandates were nonexistent. In March of 1956, the electrical industry launched the Live Better Electrically (LBE) campaign to persuade homeowners to consume more electricity. This campaign was waged through television ads, print ads and an attractive incentive aimed at homebuilders to build all-electric homes. Ronald Reagan, who was host of the “General Electric Theater”, became the perfect spokesman for the Live Better Electrically Campaign (LBE), bringing the electric industry’s message to families around the country through their television sets.

Living in a Gold Medallion home was marketed as the apex of modern living where appliances were all-electric. To heighten their modern, futuristic feel, many all-electric homes had unusual amenities such as electric curtain rods and baseboard heating, as well as very specific task lighting such as a pedicure light under a woman’s dressing table.

In and around Phoenix, Salt River Project (SRP) jumped on the Living Better Electrically bandwagon and made some exaggerated claims about “total electric living,” proclaiming that it was cleaner, healthier, and safer than living in a gas home. The most outlandish claim, which has now proven to be patently untrue, was that all-electric homes are more energy-efficient and therefore less costly to operate than their gas-powered counterparts.

Something that the electrical industry didn’t want homeowners to know is that gas ranges, furnaces, clothes dryers, and water heaters are much more energy-efficient, and less costly to operate than electric-powered appliances. According to an August 13, 2001 Los Angeles Times article by Andre Weltman, that year an all-electric homeowner in California paid an average of $2572 annually for power compared to $1108 paid by a homeowner who lived in a mostly gas-powered home. In fact, all-electric homes turned out to be such energy hogs that utilities in California have a special discounted rate for customers who live in them to help ease the burden on homeowners.

With 20/20 hindsight it is easy to see the drawbacks of the all-electric home, but in the 1950s it was hard to imagine why we shouldn’t maximize the use of something that made life so much easier. Paired with the optimism shared by most people at the time, Ard Hoyt, a Valley home builder, eagerly embraced the all-electric home and incorporated the campaign into his projects.

Israel Ard Hoyt was a prolific custom home builder who built three homes a year between 1952 and 1958 under the Ard Hoyt Construction Company. One of his most famous custom homes is the House of Light, located near 40th Street and McDonald Drive (then called Bethany Home Road), on which he partnered with Salt River Project in 1958. The house was a showpiece for SRP, pushing the envelope of what it meant to live the all-electric lifestyle.

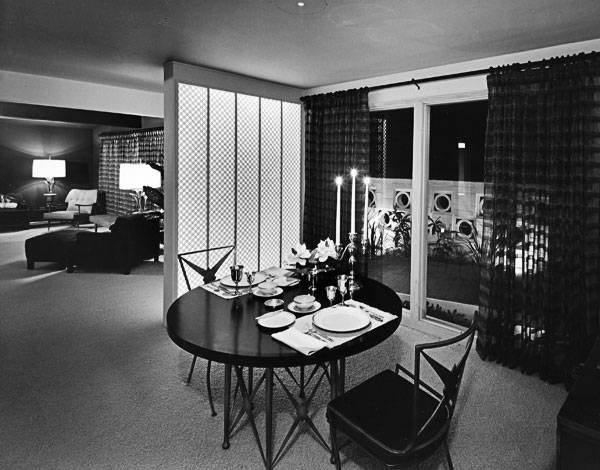

One August 1958 Arizona Homes article remarked on the home’s extraordinary lighting package: “in the living room, a dimmer light adjusts the mood from soft to bright. Dominating this room is a three unit lighting fixture of cut glass, with massive table lamps completing the décor. Elsewhere there is pinhole lighting, a wall of light, picture lighting, and in the bath, a safety pilot light for sleepy heads.”

Together with interior designer Donald J. Bondy, Hoyt made the electric lighting more than just a functional amenity in the house; he positioned it as an important aesthetic consideration for modern living. Under the guise of the heightened functionality of electricity and its ability to make life not only easier, but more beautiful, the electric industry was able to maximize its profits in partnership with homebuilders.

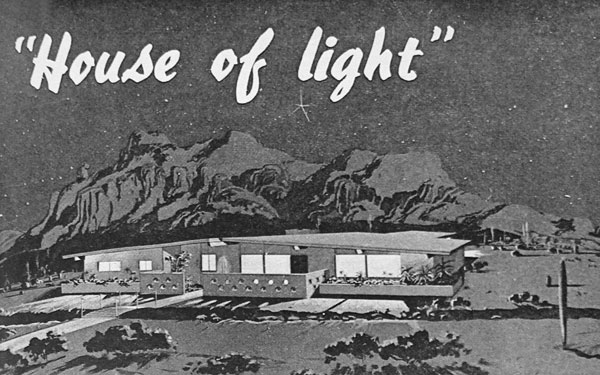

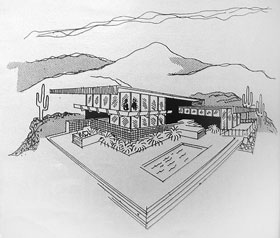

Vintage illustration advertising Open House for Ard Hoyt's House of Light

The House of Light model home was available for inspection after sunset, at 8pm to be precise, when all of its interior and exterior lights could be set blazing like a beacon. The home style was described as “Egyptian” with a Moorish patterned brise-soleil wall out front, an Egyptian statue greeting visitors on the porch and a hieroglyphic motif hung above the fire mantle. The nearby landmark Mummy Mountain is said to have been an inspiration.Built-in planters, a pond at the entrance and the low-sloped roofline — typical for the period but so unusual to Midwestern and East Coast transplants —added to the exotic experience. The name of the architect for the House of Light has been lost over time, and though Hoyt did occasionally work with registered architects it is possible the home was builder-designed as Hoyt is the only one who gets any credit for the effort.

The entryway to the House of Light is illuminated by a floor to ceiling column of light behind a fashionable grille screen. Promotional photos that follow were used in brochures and advertising, and are reprinted her with permission of current House of Light homeowners William and June Altenbernd.

Formica counters and a flush-mount range top make the All-Electric kitchen complete. The open breakfast bar concept is a pleasant step forward out of traditionally closed-off kitchens.

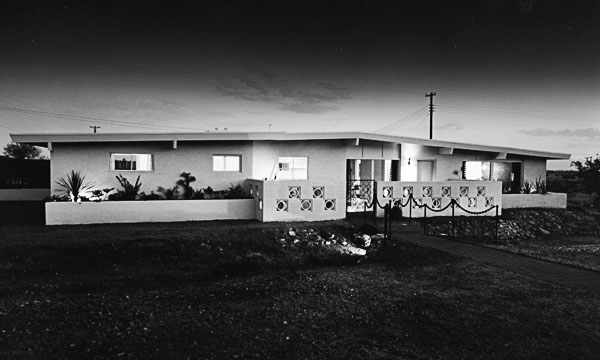

The House of Light façade in 1958, showing the wash running through the front of the property

The Egyptian decor carried through the bedroom with huge twin urn-shaped lamps. The vanity featured a pedicure light at foot level.

A much less popular albeit a truly sustainable idea for powering a home that emerged in 1958, was the Solar Home. A Solar home design competition sponsored by the Association for Applied Solar Energy and the Phoenix Association of Homebuilders was an early attempt at using renewable energy to power a house. The Solar Home, though it incorporated many sustainable practices even by today’s standards, never caught on in the mainstream homebuilding world, possibly because it didn’t have as powerful marketing engine as the Live Better Electrically campaign

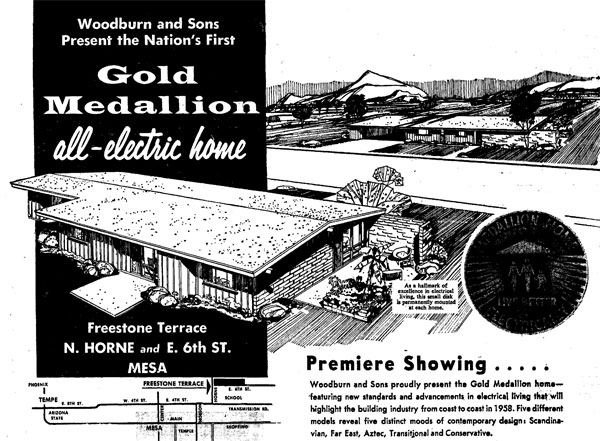

Vintage Arizona Republic Ad for a Gold Medallion Home in Mesa. Apparently Arizona is home to the first Gold Medallion all-electric homes, available in "five moods of contemporary design: Scandinavian, Far East, Aztec, Transitional and Conservative."

Hoyt’s developments were distinctive for several reasons. First, they leveraged the open desert terrain to provide a stunning setting for his homes. At Marion Estates, he incorporated the various active washes in the area into each home’s unique living experience. He was not afraid of building his homes right up against these mostly dry, but sometimes turbulent, natural waterways. “Ard Hoyt Construction Co. leaves these washes untouched, builds close to them to give the occasional exciting experience of watching nature’s forces on display from the security of homes that are as durable as they are modern,” noted a 1958 Arizona Homes advertorial. Instead of disturbing the existing washes, rerouting them, or filling them in, Hoyt integrated them into his development as a point of interest. At Lincoln Heights, he maximized the terrain in a different way using the steep slope of the mountain to create split-level homes, which were considered very desirable at the time.

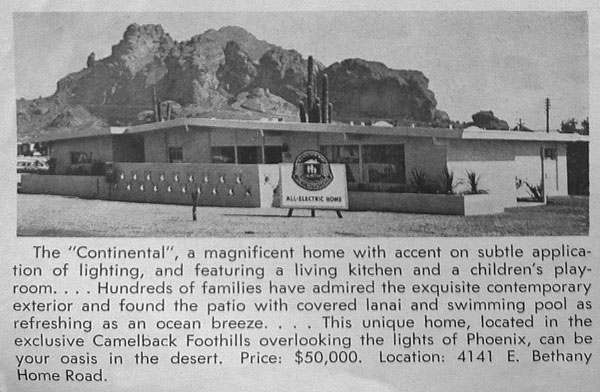

Hoyt's House of Light homes were also marketed under the names "Continental" and "Mucha Casa".

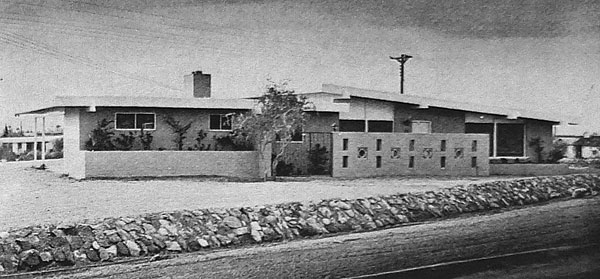

A variation on the House of Light home model, marketed as "Mucha Casa", features a different roofline but roughly same floorplan. The wash runs through the front of the property to this day.

Advertising in the early 1960s illustrates the contrast between traditional and modern lifestyles in the Camelback Foothills area

This vintage ad shows a rendering of the type of homes Hoyt sought buyers to commission in the Lincoln Heights community.

Hoyt attempted to provide a quality living experience to homebuyers through the all-electric power system. His first two instincts—the appreciation of the desert and framing of desirable views—were spot-on, and have proven to be great assets to this day, more than fifty years later. His enthusiastic adoption of the all-electric campaign, evident in his House of Light and in various Gold Medallion homes, turned out to be misguided as contemporary priorities tend towards power conservation not power consumption.

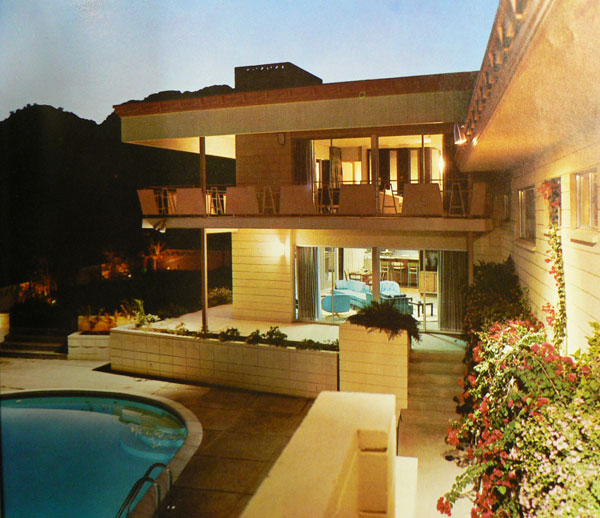

Besides their high energy bills, all-electric homes ended up having such complicated and specific electrical systems that they proved to be difficult to maintain and fix. Many Hoyt Construction Company home owners, including William and June Altenbernd who have lived in the House of Light since the 1970’s, have had to abandon the enormous and complicated electrical panel that came with their Gold Medallion home and add one that is easier to operate and maintain. This couple never took full advantage of a great deal of the intricate electrical features they found when they bought their home, such as in-house intercoms, piped-in music, and touch-button switches simply because they didn’t need them or they were hard to operate and expensive to upgrade into contemporary systems.

The House of Light in 2012, now the Altenbernd residence

If you live in a Gold Medallion Home, there are a few measures you can take to lower your electrical consumption. John Russell of RC Green Builders lives in an all-electric home that he recently remodeled to be more energy efficient. Instead of piping in a gas line to his house, which is cost prohibitive or impossible in some cases, he made his home as energy-efficient as possible. In Phoenix, the biggest source of electrical consumption is the cooling of buildings during our scorching summers. To mitigate the cooling load, Russell added more insulation, a new reflective roof coating along with a radiant barrier and upgraded his air conditioning units to 14 Seer. He also replaced the windows with more efficient ones, though Steve Shinn of Homework Remodels says you don’t need to take this very costly step, which proves to be especially costly if you replace them with historically-appropriate windows. Instead, he says, simple things like sealing air-leaks around windows and doors, adding exterior window shades, and planting trees strategically to shade the home can have a tremendous impact on your energy consumption at a minimal cost.If you simply can’t afford to make any energy efficiency improvements to your home just yet, there are some behavioral changes you can make such as using the barbecue, if you have one, as often as possible to cook in the summer so as not to heat up the house, shutting off the lights after you leave a room, hanging your clothes on a clothesline instead of using the dryer, and using appliances like the washing machine during off-peak hours.

Making your home more efficient becomes very important when you own a Gold Medallion or all-electric house. As a first step, it might be worthwhile to get an energy audit which diagnoses the ways in which you can reduce electricity consumption. Energy audits are now being offered by the Arizona Public Service (APS) and SRP for only $99 and could be well worth the price if they pave the way to reducing your monthly electric bill. Though the Live Better Electrically campaign turned out to be just a passing, but somewhat long lasting, fad starting in 1956 into and surviving into the early 70s, Hoyt’s homes have stood the test of time with their solid construction, great custom design, and masterful siting.

Hoyt died at the early age of 53 of a heart attack while vacationing in Mexico, but in his 24-year career in construction and development, he left a lasting legacy of custom homes and communities that are considered luxurious even by today’s standards.

One of Ard Hoyt's masterpieces of desert living is the Breech House in Clearwater Hills.

The Breech House interior was designed by famed local interior design leader Ron Warner of Warner's Furniture. The grille screen and floating bookshelves are custom designs by Warner.

Sources

Ads placed in the The Arizona Republic 1952 - 1963Ads placed in Arizona Homes, January 1959, August 1958

Maricopa County Recorder's Office public records

Point West, 1961

"The All-Consuming Bills of an All-Electric Home" by Andre Weltman, Los Angeles Times, 13 August 2001