- Overview

- Saguaro Models

- Custom Models

- Home Tour 2017

- Is it a Beadle?

- Ocotillo Models

- Century Models

- Tour in 2010

- Howel in 1961

- Cholla Models

- Palo Verde Models

- Home Tour 2006

- Vintage Graphics

- Photos from 2006

- Photos from 2009

- Other Models

- Receive advance notice of next year's events!

Piecing together Paradise Gardens on its 50th Birthday

Al Beadle didn't want to be cited as the architect behind Paradise Gardens in North Phoenix, so why is he still getting credit 50 years later?

By David Tyda “The architect's catch-22 is that people with taste have no money, and the people with money have no taste, so that often leaves the architect out." Thus spoke Alfred Newman Beadle in a 1988 interview with writer Gene Garrison for the Carefree Enterprise. This is a perpetual conundrum faced by many designers—the desire to make their work part of the everyday experience for many, not just the moneyed. If an architect or designer is lucky, a guy like Robert Altherr calls up one day and provides the opportunity to connect the words “design” and “masses.” Such was the case with Paradise Gardens—a subdivision of homes designed and built in the mid 1960s by Beadle and Altherr… well, kind of designed and built by Beadle and Altherr.

“The architect's catch-22 is that people with taste have no money, and the people with money have no taste, so that often leaves the architect out." Thus spoke Alfred Newman Beadle in a 1988 interview with writer Gene Garrison for the Carefree Enterprise. This is a perpetual conundrum faced by many designers—the desire to make their work part of the everyday experience for many, not just the moneyed. If an architect or designer is lucky, a guy like Robert Altherr calls up one day and provides the opportunity to connect the words “design” and “masses.” Such was the case with Paradise Gardens—a subdivision of homes designed and built in the mid 1960s by Beadle and Altherr… well, kind of designed and built by Beadle and Altherr. Around this time, Beadle (1927-1988) was working on his 22-story condominium building, Executive Towers, so he knew a thing or two about building community, not just the single-family homes and office buildings that Beadle was more well-known for. When Altherr called, though, Beadle was given an opportunity to blend the two ideas—community and the single family home. This was particularly attractive to an architect like Beadle, who was working to advance the design theories of Modernism—meaning unadorned and unapologetic architecture suited to meet the needs of both geography and daily habitation.

A devotee of Mies van der Rohe-like simplicity and rectilinear design, Beadle was gaining notoriety in design circles a pioneer of desert modernism – so much so that he was the designer behind the only Case Study House built outside California, a three-unit residence known as the Triad Apartments (it still stands today). An illustrator who worked in Beadle’s studio throughout the ‘60s, Wayne Chaney, remembers when Arts & Architecture Magazine (sponsor of the Case Study program) published the Triad in 1962. “It really got us a lot of attention,” Chaney remembers, “but,” he jokes, “they must have done their own overall illustration of it because I would have never added that many trees!”

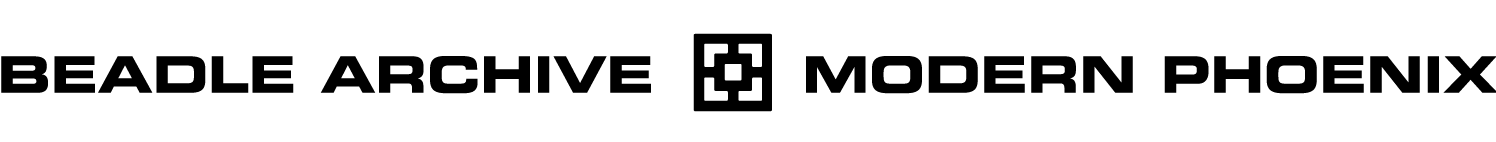

The sight of several modern-styled homes in a row was still a novelty in the the early 60s. Back then, the tract mentality of "desert landscaping" was to scrape the earth down and start fresh. The abundance of cul-de-sacs also made plenty of corner lots like the Howell's.

Though the paint and fascia have been updated, this Cholla Model home's proportions and façade are relatively intact. Most residents have chosen to stick with desert landscaping and are lucky to have mature specimens on property.

Not every project was built under such sunny skies. At some point during the development of Paradise Gardens, Al Beadle terminated his relationship to the project. This is really no secret to the current residents, whose theories lean to “value engineering” as the culprit of the split. If there's one thing that Beadle's contemporaries can agree on, it his uncompromising character. “I imagine the developer began cutting corners and that affected the integrity of the design,” says Al’s wife, Nancy Beadle. “Unfortunately, it happened all the time.”Although Chaney still possesses an original sales brochure for Paradise Gardens, he does not remember meeting Altherr or specifically working on any drawings for the development. He also doesn’t recall an Altherr-related schism raising any eyebrows around the studio. Chaney doesn’t seem to feel that Paradise Gardens was a significant commission for the studio, but it was in Paradise Gardens that Beadle could explore many of the design principles so prevalent in his custom home designs – principles still overlooked by many developers today. The homes were constructed of concrete block, not stuccoed over wood frames. They were breezy and open, allowing the inhabitants to feel the desert around them. And they were sited on fairly significant-sized lots, allowing the architecture to breathe and make its own statement.

We’ve been unable to find out how or why Robert Altherr acquired the land between 32nd and 36th Street, Mountain View and Gold Dust, or how, exactly, he came into contact with Beadle. He did have a somewhat successful track record developing and selling homes elsewhere in the Valley and purchased the Paradise Gardens tract in the late 50s.

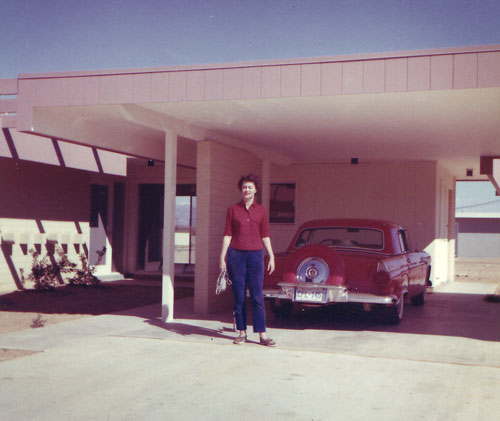

Adding an architect’s name to tract home advertising back then was almost a necessity, but Beadle's name stopped making appearances in Paradise Gardens ads as early as the 3rd week into sales.

Why the disassociation? Whether a developer was selling Ralph Haver’s Town & Country development here in Phoenix or a neighborhood by William Krisel in Palm Springs, knowing who sketched that butterfly roof was considered an amenity worth paying for. But let’s not overestimate that fact. “There were no ‘mid-century modern architects’ back then,” Sawyer jokes. “These were just tract homes, pure and simple.”In the mid-‘50s neighborhoods like Town and Country were wildly successful from a developer perspective, worth repeating as developments in Scottsdale, North Phoenix and Uptown Phoenix. Designed by Haver, these homes provided a nice balance between unique elevations and affordable repetition. Paradise Gardens was imagined in a similar vein, only that developer, Robert Altherr and his A-1 Construction, seemed to have run into a few snags.

“The buildout seems haphazard,” says Phoenix architect Ned Sawyer, who worked in Beadle’s studio between 1962 and 1972, immediately after Beadle split from Altherr. “It was strange; the roads were done first, then the homes. It’s as if they sold off pieces of land around the development in no particular order and built wherever they had a sale. There’s no evidence of building in phases or succession.”

An aerial photograph of the subdivision in 1965 illustrates the development pattern, with the eastern end of the tract almost complete, but large lots waiting to be filled to the west (top right).

And this is where questions of Beadle’s full involvement get raised. Some of the later Paradise Gardens homes were built with cheaper detailing, and marketed without Al Beadle’s name on advertising. What’s more, all original Paradise Gardens designs showed flat roofs, while pitched roof homes are popular in the neighborhood. Sawyer asks, “Does that make them not Al Beadle homes? I’m not sure. Some people have remodeled their homes in order to restore the structure back to the way they should have originally been built. Does that make a home any more of a Beadle than it was then?”

The Jones-Glotfelty Residence features a gridlike structure overhead that hearkens to Beadle's Boardwalk apartments.

Advertising for the Haver-designed Town & Country developments (which thrived and mutiplied in the mid-50s and early 60s) illustrates popular late-50s features that appear in Paradise Gardens homes: detatched or offset garages connected by overhead arbors, quartz roofs, gently pitched eaves. Even the ubiquitous circle-in-square motif cinderblock seen throughout the subdivision (but not in the brochure renderings) was referred to by Ralph Haver's partner Jimmie Nunn as "Haver Block" in its time—a decorative design that Haver designed for the Superlite company for use in Haver projects and then citywide.

Did Altherr amend Beadle’s designs to incorporate architectural moves made by his competition? Was Town & Country selling at such a successful pace that Altherr wanted a piece? Perhaps the consumers spoke, and Altherr was merely listening.As if you didn’t think that list of questions was enough, Al’s wife, Nancy, made it worse. “Oh, that’s Bob Sapp,” she told us when she saw Robert Altherr’s signature on a 1957 A-1 Construction incorporation document. We were querying her for Paradise Gardens memories when we learned that the man we knew as Robert K. Altherr of A-1 had actually changed his surname from Sapp at some point after 1954 and before developing his Paradise plans. Why this happened, we do not know. And we couldn't track down Altherr, either. But we do know that people love their Paradise Gardens homes regardless of who designed them.

View the four original elevations and compare to what they look like in today.

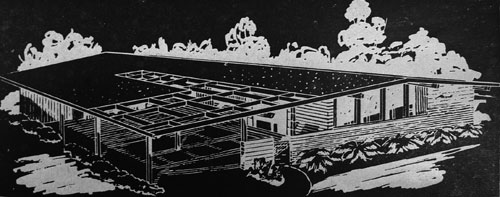

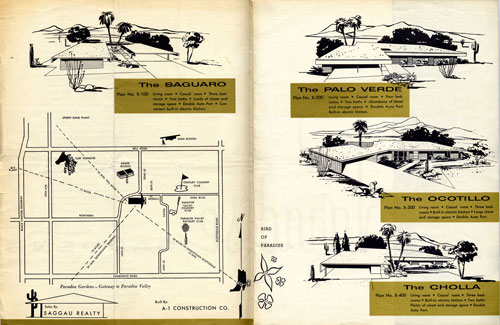

The original marketing materials for Paradise Gardens illustrate the four cactus-themed models: Saguaro, Palo Verde, Ocotillo, and Cholla. All had flat roofs and, for the most part, had similar qualities—carport, deep overhangs, and a stepping façade.

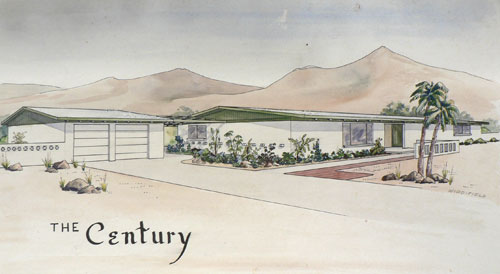

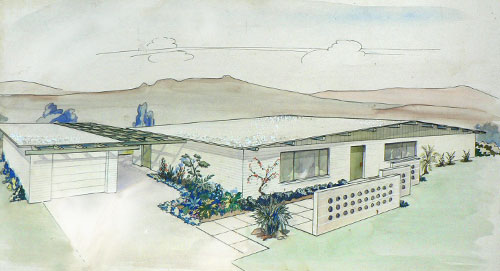

Watercolor renderings touting a fifth Paradise Gardens design called The Centurywere salvaged by residents from a neighbor's dumpster, and they're a good match for some of the alternative elevations found in the neighborhood. The Century kept with the cactus-titled theme (as in Century Plant) and came complete with a pitched roof, detatched and enclosed garage. The name Widdifield appears on one of the two mystery renderings, and Paradise Gardens resident Ulrich Hauser found blueprints citing Richard Britt as the architect when completing a remodel in the area. Britt designed the Church of the Beatitudes on Glendale Ave. but doesn't have a huge history of real estate transactions in the Valley. His construction appraisal incorporation had an office on the north side of Architect's Row (demolished) a few doors down from Fred Guirey. He may have been a part of the scene, but wasn't a big or widely-published player.

In 1963, county records show that a John Widdifield did sell a single property, Lot 89, in Paradise Gardens at 33rd St. and Onyx. The home is similar in scale to the home in The Century rendering. Widdifield's documented real estate dealings in Maricopa County were brief, as few other signigificant transactions are on record under his name. Britt's public transactions in this era are also thin.

Another home on Mountain View looks very much like The Century rendering.

Another untitled watercolor appears similar in concept to the oddball elevations shown below.

An example of the mysterious Sixth Elevation that is found dotted thorughout the subdivision.

Some homes seem a tad schizophrenic. One might have all the qualities of Beadle’s Saguaro layout, but the roof is pitched, not flat as originally designed in sales brochures. From the mid-50s onward, many tract home developers prided themselves on listening to their customers, and advertised the broad range of customization options available. Some even marketed the tract homes as designed by the customer. Periodicals of the day are filled with references to custom homes being designed by the owner in partnership with the developer. The current trend was consumer empowerment.Did the first round of homebuyers ask A-1 Construction to alter the design before it was even built, thus manipulating Beadle’s work and making it decidedly un-Beadle? Are the consumers really to blame for manipulating architecture that was designed from the start to be flexible, not fixed?

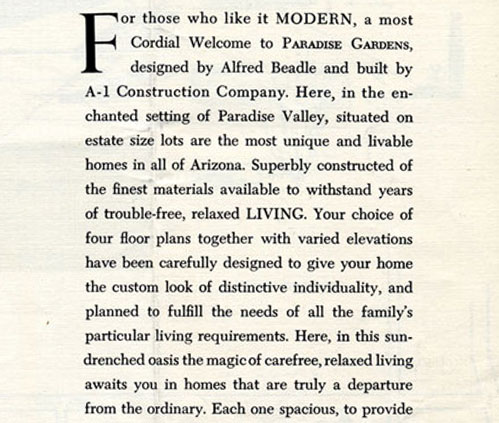

Pinpointing answers to these questions has proven to be nearly impossible – not just because of a lack of documentation, but because even those closest to what was happening in Paradise Gardens—Nancy Beadle, Ned Sawyer, Wayne Chaney—don’t remember these design alterations even remotely registering on anyone’s radar. All of which makes one wonder if Beadle really saw Paradise Gardens as a way to bring design to more people, or a simple paycheck. That question will likely never be answered. Nancy doesn’t recall hurting for money during these years, so it’s unlikely he took the Paradise Gardens job to make ends meet. One thing’s for certain: the development had its attraction. An early Paradise Gardens sales brochure that illustrated the four models reads:

“For those who like it MODERN, a most Cordial Welcome to Paradise Gardens, designed by Alfred Beadle and built by A-1 Construction Company. Here in the enchanted setting of Paradise Valley, situated on estate size lots are the most unique and livable homes in all of Arizona.”

People who live there today couldn’t agree more.Anne McCollom moved to the neighborhood in 1973 with her parents, who fled New York for the clean desert air. (Phoenix was the unofficial cure for respiratory illness back then. Now, ironically, it’s the cause of it.) Although the family moved out to escape the neighborhood downturn that happened as SR-51 was paved, they kept the home as a rental. McCollom eventually bought the property from her mother because her new husband loved those “tiny, minimalist homes.” So they began a remodel.

When State Route 51 replaced Dreamy Draw meandering through the mountain range in North Phoenix, it clipped off the western edge of Paradise Gardens and stranded its grand monument sign and tiki torch on 32nd Street. It now sits on a vacant lot.

The area has become a hotbed of novice remodelers and design industry professionals because the construction methods and original layouts lend themselves to reconfiguration and interpretation.

This remodel by DJ Fernandes of the Construction Zone turns heads on the corner of Mountain View and 35th. Of all the remodels it has possibly departed the most extremely from the original.

Stephanie Fryer, who has lived in Paradise Gardens for almost 7 years, loves the “ease of construction, the space of the lot, the block construction, the neighbors, and neighborhood,” noting that since Modern Phoenix's first tour through the neighborhood in 2006, “more modern enthusiasts have moved into the area, many with professional design/build or architectural design experience.” McCollom says that these design-savvy homeowners have “helped transform many of the homes into beautiful representations of contemporary modern living.” But are they remodeling Beadle homes or homes in a Beadle neighborhood? Fryer says, “Whether our house is an official Al Beadle or not could be disputed … Regardless, our house has the same design details as other Beadle designs in the earlier sections of the neighborhood: block construction, angular design in the rooms, ample natural light, flat/slightly pitched roof, the T1-11 siding around the top, the 30-inch north and south soffits, and the circle block used to fence our front yard.”

The neighborhood's proximity to the Phoenix Mountain Preserve and lush, 50-year old landscaping is a huge draw for new residents.

The design attribution dispute could potentially hurt the neighborhood’s declaration as historic, should it seek that designation. Plus, research could lead some homeowners to learn that they, in fact, do not live in an Al Beadle. To residents Mike Dunlop, Rick Phillips, and many others who purchased within the last 12 years (since Beadle’s death), the homes were marketed as designed by Beadle. If indeed evidence can be found that not all of these homes came from his studio, there could be significant backlash to the realtors who marketed and sold these homes, not to mention a kiss-goodbye to historic designation. But it’s a commonly known fact that Beadle disassociated himself from the development while it was in progress, so any serious action is unlikely. Twelve-year resident Marie Jones says, “the designs retain wonderful modernist qualities, even if they didn't match Beadle's hopes.”On the positive side of going historic, the area would be protected from greedy, backhoe-frenzied developers who could ruin the ‘hood forever. It would also offer residents tax breaks and restoration incentives. (Fryer notes that her taxes rose 44 percent last year. Owners of historic properties currently receive a healthy tax reduction with the caveat that they maintain and repair historic qualities.) On the less-desirable side, historic designation would limit the creative freedom currently enjoyed by residents to remodel at will. There’s no question that one of Paradise Gardens’ defining characteristics is how homeowners have renovated these homes in such distinct ways. The shapes and sizes may be the same, but the materials, detailing, and presentations are all completely different.

The Patterson-Montoya Residence has a one-of-a-kind feature: the carport structure swings on a pivot and is repositionable from front yard to back. Innovations like this tell the story of technical innovation and desert living in the Space-Age 1960s.

Paradise Gardens turned 50 years old in 2010. For preservationists, this is a milestone. The question then becomes: should Paradise Gardens residents seek historical designation for their neighborhood as a whole or for individual homes? Jones is interested in pursuing historic overall designation because it’s been known to improve, or at least stabilize, property values. But Ned Sawyer wonders if that’s even possible: “I don’t think you could pass the whole neighborhood – the homes are too different now.”On that question of remodeling at will, Sawyer says, “People should be able to remodel however they want … We’re coming from a reference point where our needs have changed, so you should be free to interpret. I mean, your home is not a Duesenberg.”

It’s exciting that here we are, on the 50th anniversary of the first recorded sale of Paradise Gardens property in 1960, and how it all went down still has its elements of mystery. What originally started out as your average, affordable tract home development (properties for about $18,000 apiece) became one of the most architecturally distinct and sought-after neighborhoods in the Valley — not just for its early roots, but for what its colorful residents have done to make it their own.