The Blaine Drake Archive

- Index

- Blaine Drake

- Beck House

- Richert House

- Hulda Drake

- French House

- Manker House

- Unitarian Univ.

- Scoville House

- Admiral's House

The Scoville House by Blaine Drake: A Requiem in Shades of GrayHow Phoenix lost a rare custom home to marketing, monsoon and miscommunicationBy Walt LockleyWith original photos by Frank Gaynor, reprinted with permission There was nothing typical about Blaine Drake's 1958 Scoville House at 5343 North 22rd Street, with its interior curved walls. It was one of his best. And now it's gone. Drake was an imaginative and versatile architect, full of ideas, responding to the individual personalities of his clients. Many architects claim connections with Frank Lloyd Wright, but Drake's credentials are impeccable. There were 140 to 160 Drake private houses out there once, all custom, each with its own varied surprises. So it's painful to report that the Scoville House was obliterated in full daylight on September 9, 2008, in its 55th year, days before this article was filed. As John Jacquemart told me, "For Phoenix, for this time period, the era, the uniqueness, the setting, this was an important work. I guess I thought it would always be there." Here's why it was important, and why it didn't make it.

The Scoville House, ready for its close-up in Arizona Days and Ways magazine

Out of the Taliesin FoldDrake spent eight years with Wright. Born in Ogden Utah in 1911, he was in the original crop of 23 half-starved apprentices of October 1932 in the Wisconsin countryside, one of the few who remained and proved useful for a long time, one of those who witnessed the plans for Fallingwater spill out of Wright's head in 140 minutes. He married fellow apprentice Hulda Brierly in a romantic quasi-tribal Taliesin wedding, returning from their ceremony to find their room cleaned and strewn with plum blossoms. He was the construction supervisor for the 1939 Bazett house, and he and Hulda were in that caravan of artsy settlers who made that first pioneering trip to Arizona.Physically, Drake resembled a younger Wright, with that high forehead and an amused patrician look in the eye. Their voices sounded alike, which he used to tease —frighten— some of the other apprentices. With that sporty name, it seems appropriate that Mrs. Wright appointed Drake as house chauffeur at Taliesin. It's easy to imagine "Blaine Drake" grinning with a full head of wind-whipped hair, piloting one of their long Lincolns. Drake left the Taliesin fold on good terms in 1941. After a brief stint in Albuquerque, he started practice in Phoenix in 1945, built a large number of good houses and a couple of minor landmarks, and accumulated some measure of international acclaim. His major single work was the Unitarian Universalist Church at 40th Street and Lincoln. Drake's other larger projects included a big remodel for the Heard Museum in 1958, and work in the 1960s for the Camelback Inn, including the design of that rocky, gnomic little John C. Lincoln chapel. His connection to the local Taliesin fold was a mixed blessing, with uncomfortable political problems as an ex-apprentice and competitor to Wright. According to his own unpublished autobiography, he couldn't win. Any error on his part brought uncomfortable attention, and any success brought intrusive envy. This was more than a professional relationship. Hulda and Blaine's four kids had been raised at Taliesin. Finally, in the mid-1950s, Drake became involved in a job that Wright that priced himself out of, the Phoenix Art Museum. For this the Drakes were excommunicated from the Fellowship in the mid-Fifties, and cut off from their entire network of old friends and colleagues. Further, one letter in the archive indicates that Drake was in hot water with the Phoenix AIA in the early 1950's, a terse typewritten letter saying, essentially, "You're misbehaving, so please come to the next meeting." He was officially on the outs with the AIA after 1975 for his design-build practices, frowned upon then. He practiced for ten more years with 'builder and developer' on his letterhead. There's more to this story we don't know, but as far as being at odds with the Phoenix AIA, we know that Drake was in the best possible company with many other maverick architects and designers who did not play by their rules. Surmounting all these problems, Drake was productive for four decades. Drake retired in 1985, and died in 1993.

House ThinkingIf there's one hallmark of Drake's residential work, it's the customization, the obvious number of decisions-per-square-foot. This is completely different territory than the tract home architects of the industry, who duplicated the same economical designs thousands of times, which are obvious from the street, and who expected—wanted—their clients to adapt to their own uses. In contrast to them, Drake started fresh every time, and produced tailored solutions. Drake may have even influenced the growth of the city, to some small degree. According to John Jacquemart's interview with developer Larry Burke, home buyers were attracted to Bartlett Estates in the Biltmore area, in north Phoenix, because of the cluster of five or six Drake houses there. These generous horse properties, with lots of attractive land and great architecture set into it like gemstones, all this amounted to a complete prepackaged lifestyle. This Drake cluster included his first house in Phoenix, the Chase-Alden house at 5348 North 24th Street (long gone), his own 1954 house at 5210 North 22nd Street (still there), the Owen Residence at 5326 North 24th Street (razed), and the Harold Scoville House (where the dust is literally still settling).

Drake may have even influenced the growth of the city, to some small degree. According to John Jacquemart's interview with developer Larry Burke, home buyers were attracted to Bartlett Estates in the Biltmore area, in north Phoenix, because of the cluster of five or six Drake houses there. These generous horse properties, with lots of attractive land and great architecture set into it like gemstones, all this amounted to a complete prepackaged lifestyle. This Drake cluster included his first house in Phoenix, the Chase-Alden house at 5348 North 24th Street (long gone), his own 1954 house at 5210 North 22nd Street (still there), the Owen Residence at 5326 North 24th Street (razed), and the Harold Scoville House (where the dust is literally still settling).

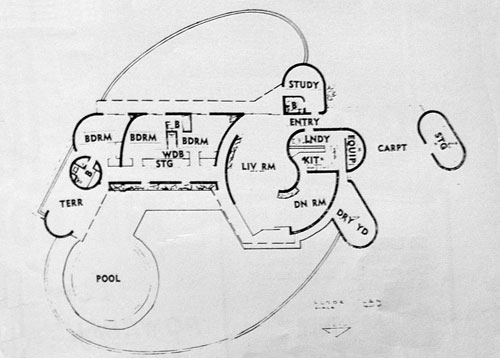

What do all these Drake houses have in common? Not much.  At least two of these had curvy, streamlined floorplans with "walls conforming to the lines of traffic." At first glance, you might conclude that in the postwar years the whole of life was accelerating, and society demanded that your wife and kids would all be whizzing through the house at high velocity. A closer look at the Scoville floorplan reveals something much smarter going on. There's a perpetual tension between curves and straight lines in a floorplan: curved surfaces are humane and complicated and desirable, but curves are also expensive, problematic for contractors, difficult for furniture.

At least two of these had curvy, streamlined floorplans with "walls conforming to the lines of traffic." At first glance, you might conclude that in the postwar years the whole of life was accelerating, and society demanded that your wife and kids would all be whizzing through the house at high velocity. A closer look at the Scoville floorplan reveals something much smarter going on. There's a perpetual tension between curves and straight lines in a floorplan: curved surfaces are humane and complicated and desirable, but curves are also expensive, problematic for contractors, difficult for furniture.

Drake's heyday in Phoenix saw a lot of round buildings erected, both commercial and residential, culminating in Wright's spectacularly impractical late house designs like the David Wright House and the Lykes House. Drake's Scoville House is a brilliant essay in curve vs. line compromise. In plan the curves are both regular and irregular, something like pond ripples that wordlessly indicate the social center of the house. There's a certain dynamic effect inside the curve, and outside on the street, that convex grid of Superlite block communicated containment and solidity, like a little fortress. A completely different example of Blaine Drake's aesthetic is the French House, not far to the west. Built in 1954 for the eye doctor and Mrs. Harry J. French, recently owned by designer Troy Bankord, this single-family residence at 411 East Missouri carries a mid-1950s sense of elegance and breezy artificiality evoking, oh, Douglas Sirk. It's an elaborate wood frame house loaded with built-ins and amenities. This house suggests an entire vanished lifestyle, a spread out loose rhythm, exposed to sunlight and air, completely engaged with the climate.  There are pocket doors everywhere – with the pocket doors you could section off any room in the house. Between the kitchen and the dining room are two-way cabinets, and countertops with sliding partitions, suitable for making the kitchen disappear completely. (Troy reminded us, "Well, they would have had help.") The floorplan is spacious and relaxed, with an open relationship to the patio and back yard. All the brickwork is mortared in a certain way, with deep horizontal grooves and filled-in vertical grooves, to visually emphasize its horizontality. This is an old Wright trick, they tell me. Troy said the house is constantly surprising him. He and Blaine Drake are still talking to each other, figuring each other out, and the amount of thought and care reflected in these amenities tells you a lot about Drake as an architect.

There are pocket doors everywhere – with the pocket doors you could section off any room in the house. Between the kitchen and the dining room are two-way cabinets, and countertops with sliding partitions, suitable for making the kitchen disappear completely. (Troy reminded us, "Well, they would have had help.") The floorplan is spacious and relaxed, with an open relationship to the patio and back yard. All the brickwork is mortared in a certain way, with deep horizontal grooves and filled-in vertical grooves, to visually emphasize its horizontality. This is an old Wright trick, they tell me. Troy said the house is constantly surprising him. He and Blaine Drake are still talking to each other, figuring each other out, and the amount of thought and care reflected in these amenities tells you a lot about Drake as an architect.

Another significant house is the five-bedroom Dr. Raymond Manker House in Paradise Valley, circa 1964, 2900 square feet, designed for the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation. The wraparound deck on the west side cleverly integrates the house to its site, true to the organic tradition, and the details, realtor Scott Jarson says, are "flawless, crisp, fantastic; it represents a point in time where postwar modern grew up into mainstream design."

Another significant house is the five-bedroom Dr. Raymond Manker House in Paradise Valley, circa 1964, 2900 square feet, designed for the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation. The wraparound deck on the west side cleverly integrates the house to its site, true to the organic tradition, and the details, realtor Scott Jarson says, are "flawless, crisp, fantastic; it represents a point in time where postwar modern grew up into mainstream design."

Unlike the Scoville House, the sale comes with some conditions: "The home is not to be significantly modified and demolition is strictly prohibited. This rare example of a pristine, unmodified home designed by Mr. Drake is a superb find and should be acted upon accordingly."

Unlike the Scoville House, the sale comes with some conditions: "The home is not to be significantly modified and demolition is strictly prohibited. This rare example of a pristine, unmodified home designed by Mr. Drake is a superb find and should be acted upon accordingly."

Which leads us to the Drake / Beadle House, on Stanford Drive west of 40th Street. In nearby Paradise Valley, on a rocky desert site with a view to the south, this one began life in 1955 as a panel house on concrete pads, and constructed in two parts, separated by the carport. So you'd have to go outside twice a day at least. If nothing else, it demonstrates Drake's versatility – it's nothing like the other houses. You imagine the house surrounded by 1955's scrub, in timeless vacation days filled with long desert explorations towards the mountain, the round pool waiting for when you got back, a turntable and thick long-playing George Shearing and Herbie Mann platters you'd carefully keep out of the late-afternoon sun. This one was remodeled by Al Beadle in 1966, who enclosed the carport. With an informal, inexpensive, even underbuilt quality, it's very oriented to the outdoors and seems like a beach house, a long long way from the beach.  Photo © Joel Contreras 2007

Drake's Meaning in PhoenixWith all this variety, certain features are consistent across Drake's house designs.These were plush, custom-designed houses at the time of their creation. Drake certainly cared about people's personal needs and the psychological effect of his spatial design, titling one of his magazine pieces "Maximum Livability", writing elsewhere that "We should recognize the importance of the impact of our houses upon our emotions, however subtle it may be." Most of them use local materials, like pumice block, in the most unadorned way. Again, true to the organic tradition. Regardless of materials, most of them feature a Wrightian spatial feel, with a hearth as locus, and huge emphasis on common social areas at the expense of the relative size and position of the bedrooms. The Drake house in particular was designed for entertaining in the era of the elaborate cocktail party, Peter Drake reminded me, with 100 guests arriving at once and spilling into the yard.  And they're almost effortlessly sensitive and cooperative with the Arizona desert for "winter warmth and summer shade". Drake knew the desert. As a Wright apprentice he'd logged plenty of man-hours in extreme conditions under the canvas tents at Taliesin, and his son remembers a sun-angle calculator forever on his desk in his own drafting room at home, a room submerged 2/3rds below grade. He knew what he was doing in the desert, and his true legacy might be that certain lessons—about orientation, west-wall fenestration, airflow, using masonry mass as heat-batteries, etc.—have been carefully studied and internalized and recycled by another generation, people like Eddie Jones and Will Bruder, who has spoken admiringly about Drake's exploded spaces. There are actually some indications here that desert architecture is getting somewhere.

And they're almost effortlessly sensitive and cooperative with the Arizona desert for "winter warmth and summer shade". Drake knew the desert. As a Wright apprentice he'd logged plenty of man-hours in extreme conditions under the canvas tents at Taliesin, and his son remembers a sun-angle calculator forever on his desk in his own drafting room at home, a room submerged 2/3rds below grade. He knew what he was doing in the desert, and his true legacy might be that certain lessons—about orientation, west-wall fenestration, airflow, using masonry mass as heat-batteries, etc.—have been carefully studied and internalized and recycled by another generation, people like Eddie Jones and Will Bruder, who has spoken admiringly about Drake's exploded spaces. There are actually some indications here that desert architecture is getting somewhere.

The Scoville TeardownThe downside of Drake's design variety is that there's no natural constituency of Blaine Drake owners. If there had been, maybe the Scoville House would still stand.Admittedly, before I spoke to the owner of the Scoville House, I had the final part of this story already outlined. Something about classic mid-Century houses being tiny and inconvenient and stale for today's bulldozer owner, something about SUVs and Tuscan McMansions and thoughtless dominance, a familiar master narrative you might already be able to name in three notes. Instead, let me offer a conclusion that's a little more ambiguous and a lot closer to reality. His name is Jack Kannapel. Although I warned him that he was viewed as a villain in some parts, he was open about his experience, talking from his local sports retail shop. When Jack acquired the house, he had no idea it was a Blaine Drake, although there was an obvious Wrightian influence. On learning about Drake he held off on the planned teardown, and started gathering information. He contacted Blaine's son, Peter, his neighbor about a block away. Jack was quick to tell me that he grew up in Mesa, so he can't be summarily dismissed as an outsider. And he tried to have the right conversations with the right people about how much of this house was savable. Because there were issues. The house was built at grade, a literally fundamental problem. Every rainstorm was a new disaster. There's no good answer for that: previous owners had put in a surrounding berm but the true solution would have been extensive and expensive landscaping. (Interestingly, though, Scott Jarson says this isn't unusual at all. Houses of this era were commonly built just at grade, and fifty years of Arizona dust storms have deposited new surface around the house, something like what happens at an archaeological site. Four inches is a common figure. When you get this, you just have to spend the money and adjust "the topo".)  Further, though, there were bad roof issues, a roof that sagged towards the middle and collected water, and during demolition the rafters exploded under pressure—a sign of terminal rot. The elastomeric roof had essentially melted onto/into the rafters. This plasticky goo provided the only strength up there. And there were electrical issues. There were mold problems. According to Jack the standard of construction was below normal even accounting for the year. And during the most recent monsoon storm, a tree crashed over onto a structural wall, the last straw.

Further, though, there were bad roof issues, a roof that sagged towards the middle and collected water, and during demolition the rafters exploded under pressure—a sign of terminal rot. The elastomeric roof had essentially melted onto/into the rafters. This plasticky goo provided the only strength up there. And there were electrical issues. There were mold problems. According to Jack the standard of construction was below normal even accounting for the year. And during the most recent monsoon storm, a tree crashed over onto a structural wall, the last straw.

True, there were some unsurprising livability/design issues. The 2,600 square foot was perfectly adequate, Jack said, for two people. That wasn't a problem for him. But the ceilings were six and a half feet, the last two bedrooms were "exceptionally tiny", and there were literally no closets. A previous owner, judging from the cabinetry perhaps the first owner, had built exterior closets along the hallway, which meant two feet of clearance through there.  Hallway closets in the Scoville House, months before demolition

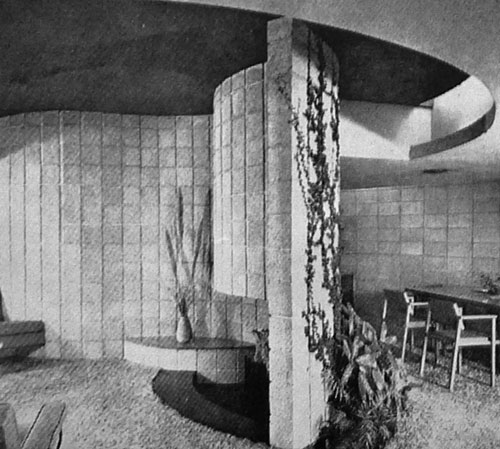

Jack talked about the good points of the house with sympathy—the skylights in what would have otherwise been a dark interior, and the rounded interior walls that gave it a lot of character. In the end, with the current market working against him for any resale, and with regret, he went ahead with his original plan and pulled the trigger. It wasn't from lack of respect or lack of knowledge.

Jack talked about the good points of the house with sympathy—the skylights in what would have otherwise been a dark interior, and the rounded interior walls that gave it a lot of character. In the end, with the current market working against him for any resale, and with regret, he went ahead with his original plan and pulled the trigger. It wasn't from lack of respect or lack of knowledge.

Hearth area in the Scoville House, months before demolition

As preservationists we have to face the unpleasant lack of a villain here. It seems everyone made considered, responsible decisions. It's hard to know exactly what went wrong. Even in the happiest cases, there are challenges associated with preserving 50-year-old modernist houses built with wit, built in the spirit of stripping away the unnecessary, built as winter playhouses, and plainly not built to last 50 years. We're up against material reality. We're also up against the rights of property owners and the perceived value of these properties, and the level of communication and coordination in our own community.

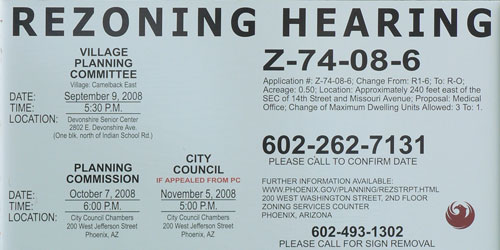

Whatever the exact lesson is, we should sort it out it fast and apply it at 16th and Missouri, a bungalow with a substantial Blaine Drake Addition that was rezoned for office space as it was up for sale. It was recently recommended for approval in re-zoning by the Village Planning Committee and was in immediate danger. Here we go again.*

Whatever the exact lesson is, we should sort it out it fast and apply it at 16th and Missouri, a bungalow with a substantial Blaine Drake Addition that was rezoned for office space as it was up for sale. It was recently recommended for approval in re-zoning by the Village Planning Committee and was in immediate danger. Here we go again.*

SOURCES "The Curved Line," on Drake's Scoville House, Arizona Days and Ways, November 22, 1953 "Design Trends of Today's Homes," by Drake, Arizona Homes and Gardens, October, 1954 "Curves for Livability," by Drake, Arizona Homes, June, 1958 "Maximum Livability," by Drake, Arizona Homes, August, 1958 Blaine Drake, unpublished autobiography, circa 1990 interviews with John Jacquemart, Scott Jarson, Peter Drake, and Jack Kannapel, September 2008 |