Bennie Gonzales FAIA: Master Southwest Architect

By Johanna Haver

This article was made possible through the generous input of Diane Hadley Gonzales, representing the estate of Bennie Gonzales.

This article was made possible through the generous input of Diane Hadley Gonzales, representing the estate of Bennie Gonzales.

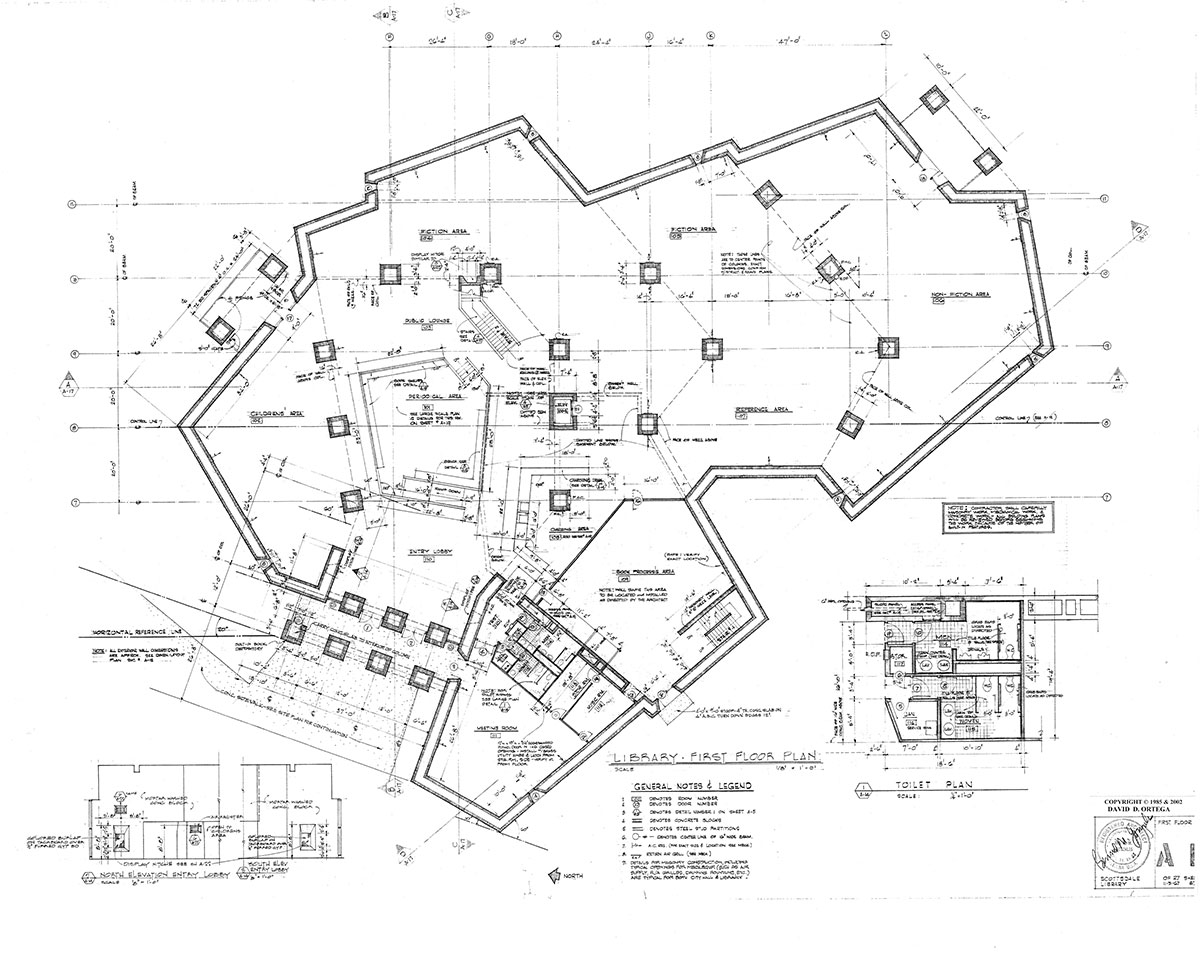

Gonzales' plans for the Scottsdale Public Library featured obtuse angles. Source: David Ortega Collection

Bennie was admired and widely emulated for his innovative, practical concepts. He frequently used angles wider than 90-degrees to open up interior spaces, and he tapered his massive columns to make them more aesthetically pleasing. He chose building materials based on their durability, accessibility and cost, rather than on trends.

Bennie sensitively captured the culture of a people by using a Navajo blanket motif and eastward hogan entrance in his design of a hospital for the Navajo Nation in Chinle, Arizona. Source: David Ortega Collection

Bennie's drawings flowed from him effortlessly, as though they had always existed somewhere in the depths of his soul. He related well to artists and builders, because he considered himself one of them. From humble beginnings, his talent took root in the Arizona soil and earned him a seat among the foremost architects of the region.

Architect Will Bruder, himself a master of form and materials, reflected on the time he heard Bennie present at Soleri Studio in 1967. By the end of the decade "Bennie's work was popularly embraced across the southwest by lay users, builders and professionals alike," Bruder recalled. "As it matured it combined material and craft as well as form and structure into sustainably comfortable and affordable habitations for a contemporary desert lifestyle. Its originality presented a sharp contrast to the glass and steel pavilions of the California rooted Arts and Architecture Case Study program, so lauded then and now. Bennie’s architecture was often more playful and his architectural response to our desert climate and ‘place’ more appropriate than that of many of his contemporaries."Childhood and Education

Bennie was born in Phoenix as "Barnaby Montague Gonzales" in the year 1924. He called his heritage "Arizona Pot Pouri:" his father, Francisco Gonzales, was German/Native American/Mexican; his mother, Guadalupe Montague, French/Irish/Mexican. Bennie inherited his dad's tall and dark good looks; at 6'2", he towered over most.His father owned a 20-acre farm in Phoenix at what is now 20th Street and Osborn while managing a saloon on 3rd Street and Washington. During the Great Depression, the family ate well because of their homegrown vegetables and livestock. Bennie recalled swimming in the canal, drying off in the sun, and then running to the fields to eat fresh watermelon. Bennie's father died when he was only 7 years old. His mother sold the farm and moved Bennie and his younger brother Frank close to relatives, near 16th Street and Van Buren. Bennie described this neighborhood as "Mexican Town," where "all the adobe workers, bricklayers and plasterers lived. So if you grow up making mud pies, it's hard to get it out of your system."

Bennie spoke Spanish at home and learned English in school. After repeating first grade, he skipped second grade and then excelled academically. He earned money for the family by delivering newspapers, sweeping out neighborhood stores, selling tamales made by his mother and grandmother, and helping out at his uncle's adobe-brick factory. According to Bennie, "Everyone in my family was in construction." Santiago Cahill, his uncle by marriage, was a contractor who helped build the Heard Museum, Paradise Inn, Camelback Inn, and Arizona Biltmore. Often he took Bennie along to the construction sites. While visiting the Biltmore site, an 8-year-old Bennie saw Frank Lloyd Wright. He was so impressed by the respect the workers showed Wright that he decided to become an architect himself.

Acting as a mentor, Cahill encouraged the boy, "Bennie you can and should become an architect." His first gifts to him were building blocks and a hammer. Under Cahill’s supervision, Bennie built his first house for a family member when he was only 15 years old. This dear uncle, the brother-in-law and close friend of Bennie's deceased dad, treated both Bennie and his brother Frank with the same fatherly love and interest that he showed his own eight children.

The Arizona Medical Association building at 810 West Bethany Home Road, designed by Bennie Gonzales

During many summer vacations, Bennie took the train from Phoenix to visit his maternal grandmother in Nogales, a small Arizona town at the Mexican border. His grandfather, George Montague, had been chief engineer for the Southern Pacific. Bennie came to value his heritage and the beauty of the old adobe buildings in this southwestern setting.Bennie faced discrimination in Phoenix. Bennie and his brother Frank had to sit in the back row of the movie theater with the other Mexican children. They were permitted to swim in the community pool, but only on Wednesdays, before the pool's weekly evening cleaning. When seeking to buy a lot for his first house, Bennie was told that deed restrictions forbade the selling of the property to Mexicans - a rule that he helped rescind. Bennie refused to let prejudice discourage him.

The day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Bennie joined the U.S. Coast Guard. He was 17 and had been attending Phoenix Union High School. His recruiter talked him into permanently changing his name to "Bennie M. Gonzales." The military sent him to places halfway around the world where he was able to examine the architecture of various ages and societies. During those years, his mother died.

As much as Bennie loved the cities he had visited, he longed for the Arizona desert so returned there at the end of the war. In 1947, he married Lupe Baca and shortly thereafter enrolled in college. In 1953, he was one of the two first graduates of the newly established School of Architecture at Arizona State University (ASU). While studying at ASU, Bennie took temporary jobs that included cabinet-making and home renovation. As a part-time Phoenix firefighter for 5 years, he noticed how fast wood burned as opposed to fire-resistant concrete block and adobe sun-dried bricks—a detail important to his future career.

Mortar-washed slump block features Gonzales' own off-white blend at Gloria Dei Lutheran Church in Paradise Valley.

Upon graduation from ASU, Bennie accepted a grant to attend the University of Mexico Architectural School in Mexico City from 1954-5. His wife Lupe and 2-year old son Barney James, nicknamed "BJ," accompanied him. In a memoir, Bennie recalled, "The history of Mexico and the ancient work of the Mayans and Aztecs were illuminating to me of the work possible by the early indigenous people." He admired the work of Mexican contemporary architects Felix Candela and Luis Barragan.After returning to Arizona, Bennie continued postgraduate studies at ASU. In the mid-to-late 1950s, he worked for various local architects: James Elmore, the founding dean of the ASU College of Architecture; Blaine Drake, a former apprentice with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West; Ralph Haver, an up-and-coming Phoenix modernist; and others.

Bennie passed the exam to become one of the first Mexican-Americans officially registered as an architect in Arizona. Later, he became registered in other states: California, Colorado, Illinois, New Mexico, New York, Texas and Washington. In addition, he obtained his license as an Arizona landscape architect.

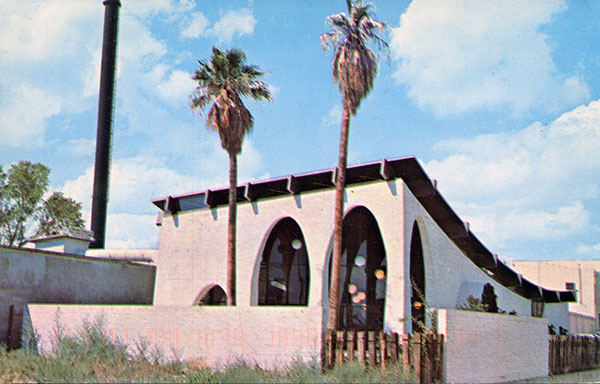

First Major Project: Library in Nogales, Arizona

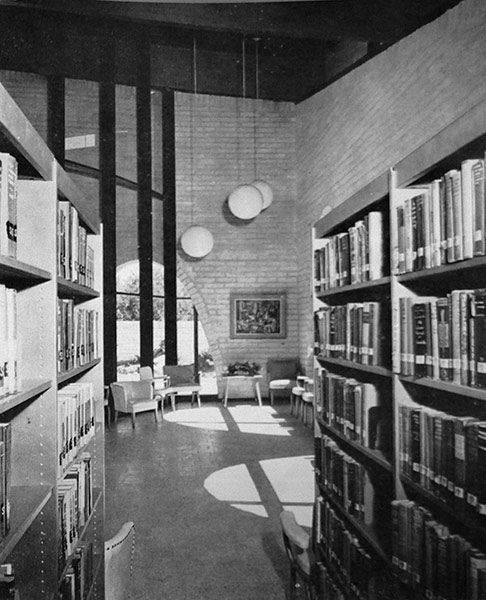

The Nogales Public Library as it stands in 2013 (above) and as it was in 1958 (below)

Interior of the Nogales Public Library

Interior of the Nogales Public LibrarySuccess in the 1960s

The early 1960s were a busy time for growth in the Phoenix Metro area and produced some of the city's most magnificent modern architecture. To meet the increasing demand for his work, Bennie found it necessary to hire several architects, sometimes apprentices from Frank Lloyd Wright's School of Architecture. In 1960, his firm became established as Bennie M. Gonzales Associates Incorporated. His team's projects included homes, churches, government buildings, medical centers, museums, office complexes, resorts, restaurants, schools, and stores.In 1961, Bennie's firm designed the Gloria Dei Lutheran Church in Paradise Valley, a town near Phoenix. Made of slump block with a painted mortar wash, the structure reaches dramatically upward. Its graceful simplicity draws attention to its recessed, elongated, arch-shaped stain-glass windows. As light shines through these openings, a blue hue cools the interior.

Interior of Gloria Dei Lutheran Church in Paradise Valley by Bennie Gonzales

Centers of Worship by Bennie Gonzales

- Christ Church of the Ascension, Paradise Valley

- Gloria Dei Lutheran Church, Paradise Valley

- Har Zion of the Desert, Paradise Valley

- St. Stephens Episcopal Church, Phoenix

- Scottsdale Bible Church, Scottsdale (now Temple Solel)

- St. Elizabeth Seton Catholic Church, Sun City

- Church of the Epiphany, Tempe

- Desert Haven Community Church, Tempe

- St. Pius X Catholic Church, Tucson.

Bennie worked on multiple projects in Litchfield Park, Arizona: the Litchfield Park Development, Tierra Verde Village Center and Jardin del Oeste Patio Homes. The town's historical society has praised him for his adobe style, use of recycled materials and attention to energy conservation. These structures resulted in awards from the AIA, House and Home Magazine and American Homes Magazine.

Scottsdale Bible Church is now Temple Solel on McDonald Drive in Paradise Valley. Its soaring spirit is similar to his Nogales library.

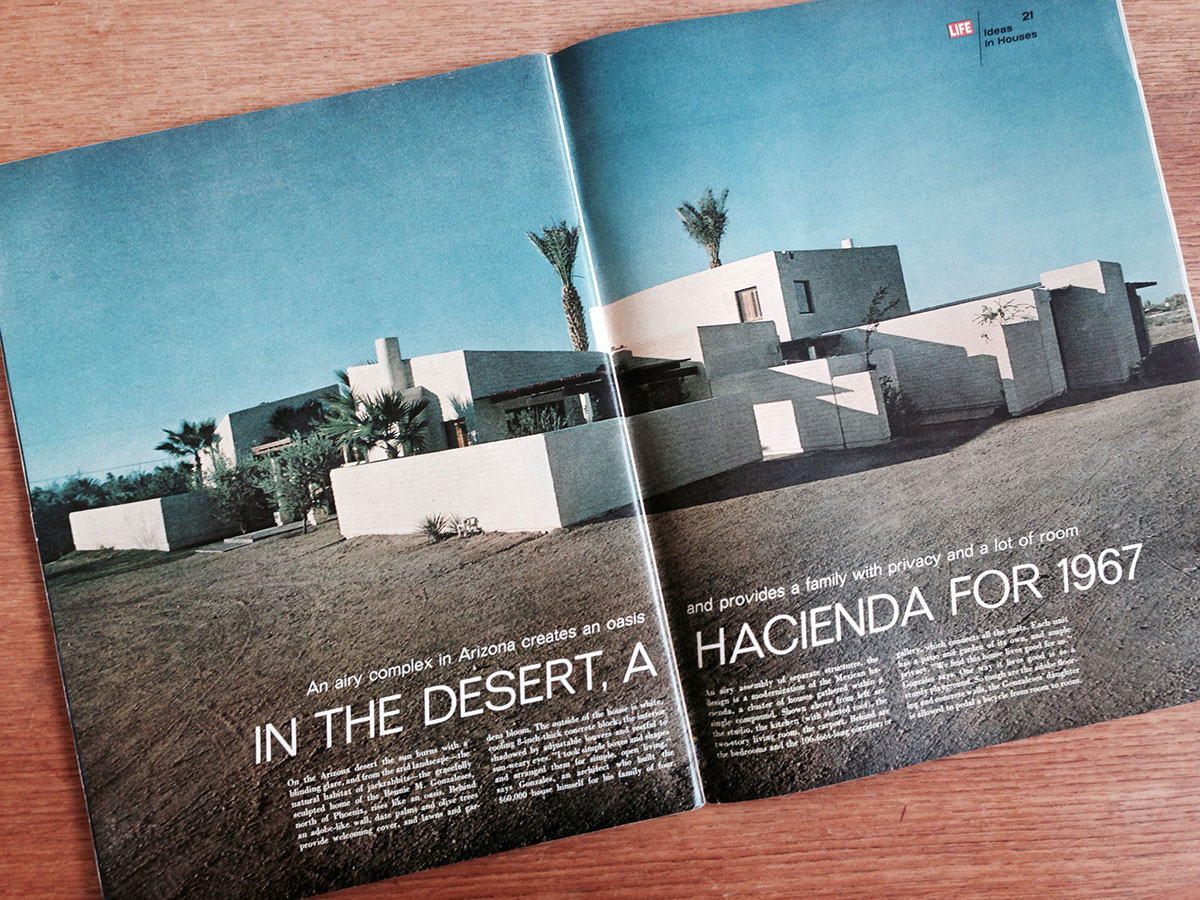

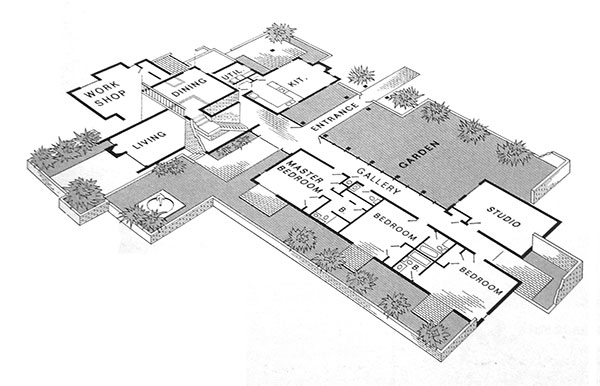

In 1966, Bennie renovated a 1930s hacienda for his family - now including his 5-year old daughter Bianca and BJ, 14. The AIA and Architectural Record Magazine presented him with awards for his renovation. Life magazine praised him in a 6-page feature article (February 10, 1967) for having turned an elaborate adobe mission-styled structure of the 1930s into "an airy assembly of separate structures" and "a modernization of the Mexican hacienda, a cluster of houses gathered within a single compound."

In 1966, Bennie renovated a 1930s hacienda for his family - now including his 5-year old daughter Bianca and BJ, 14. The AIA and Architectural Record Magazine presented him with awards for his renovation. Life magazine praised him in a 6-page feature article (February 10, 1967) for having turned an elaborate adobe mission-styled structure of the 1930s into "an airy assembly of separate structures" and "a modernization of the Mexican hacienda, a cluster of houses gathered within a single compound."

Bennie explained, "I took simple boxes and shapes and arranged them for simple, open living." Bennie used slump block with a painted mortar wash. Rather than sketch plans for the project, he drew lines directly on the ground for the contractor to build from. Bennie had worked with him before and, thus, trusted his understanding of the building process. With no client to please, Bennie was able to organize the home informally so it evolved out of the original site in a natural way.

Bennie explained, "I took simple boxes and shapes and arranged them for simple, open living." Bennie used slump block with a painted mortar wash. Rather than sketch plans for the project, he drew lines directly on the ground for the contractor to build from. Bennie had worked with him before and, thus, trusted his understanding of the building process. With no client to please, Bennie was able to organize the home informally so it evolved out of the original site in a natural way.

Bennie Gonzales (top right) served as an officer in the Central Arizona chapter of the AIA in 1963

In 1967, Bennie renovated and doubled the size of the Heard Museum - a center focused on the Native American heritage, cultures and arts; and, a building that his uncle and mentor Santiago Cahill had worked on. It is one of the city's 33 landmarks designated a "Phoenix Point of Pride." The Heard's special features include an arched entry and covered walkways that face onto an open courtyard.In the late 60s, Bennie competed with 36 firms to create a plan for a Scottsdale civic center that would include a library and city hall. The purpose was to provide an area where people could congregate to learn, appreciate the arts, and discuss civic issues.

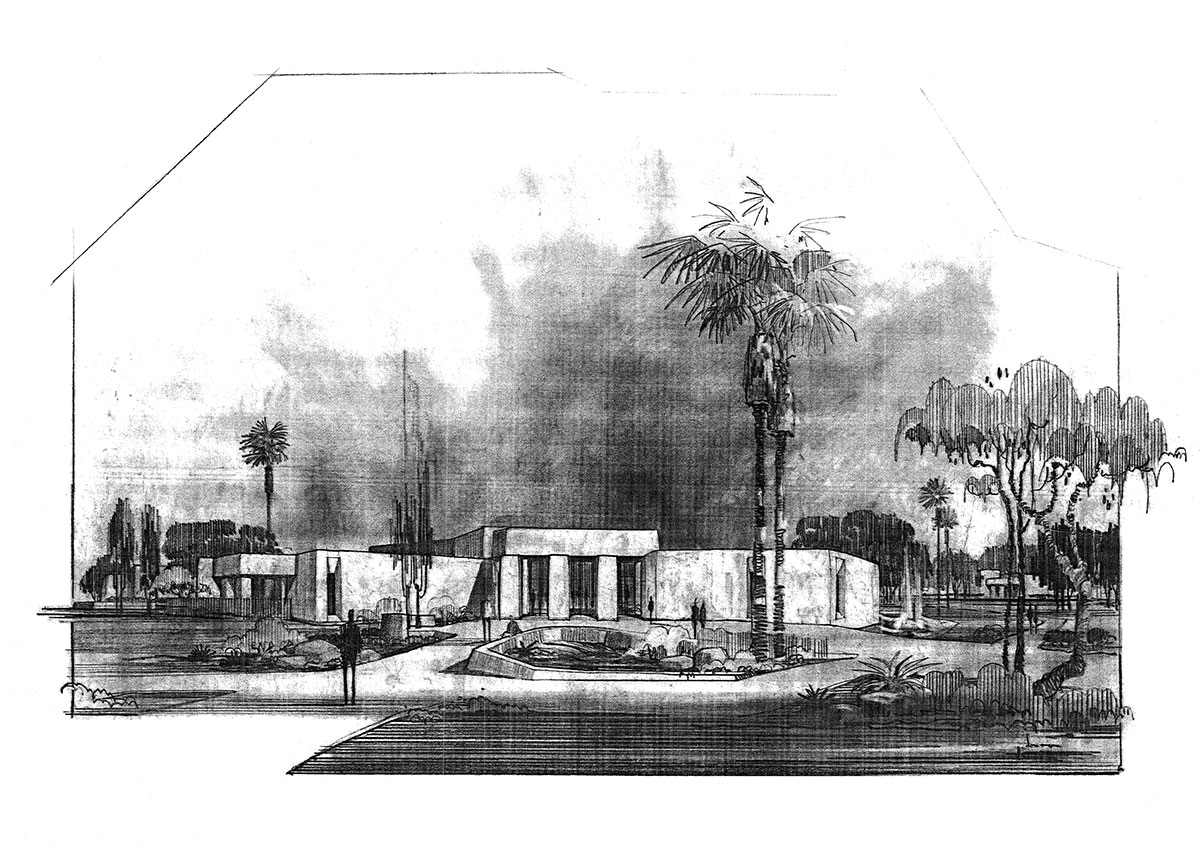

An artistic rendering of the Scottsdale City Hall. Source: David Ortega Collection

Noteworthy 1960s structures by Gonzales

- Eloy Junior High School, Eloy

- Douglas Mansion: Mining Museum, Jerome

- VFW Hall, Nogales

- Valley National Bank, Nogales

- Southwest Produce Center, Nogales

- Los Cuatros Apartments, Scottsdale

- Western Savings & Loan, Yuma

- Anderson Apartment Complex, Yuma

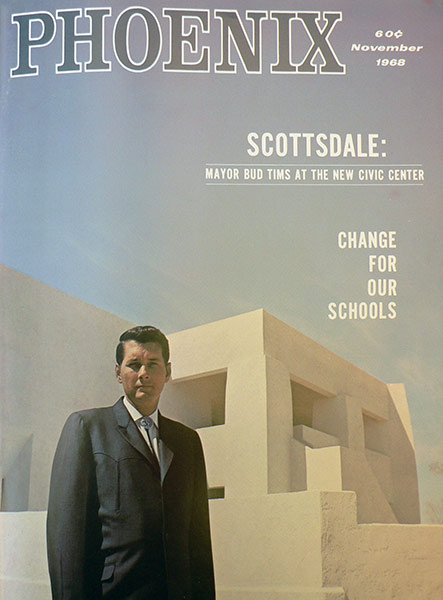

Bennie designed the civic center to be inviting and easily accessible to the public through its many entrances. The sculpted, adobe-styled, double-thick concrete walls and recessed windows of the civic buildings are both appealing and protective from the summer heat. Existing shades of white were too bright for the effect he wanted, so he formulated his own "Navajo white" paint. The open interior of city hall is circular with a recessed floor, modeled after the Native American Kiva, and ideal for gatherings and civic dialog. The ceiling lets in light through colorful stained glass panels that were created by local Scottsdale artisan Glassart Studio.

Harper's Magazine praised the structures, "The Scottsdale City Hall and Library are a pair of the most gratifying and under publicized civic buildings in America." (December 1969). They received three AIA awards. The Scottsdale Public Library entry way and interior have since been altered, but the City Hall remains relatively intact.

More Success in the 1970s and early 1980s

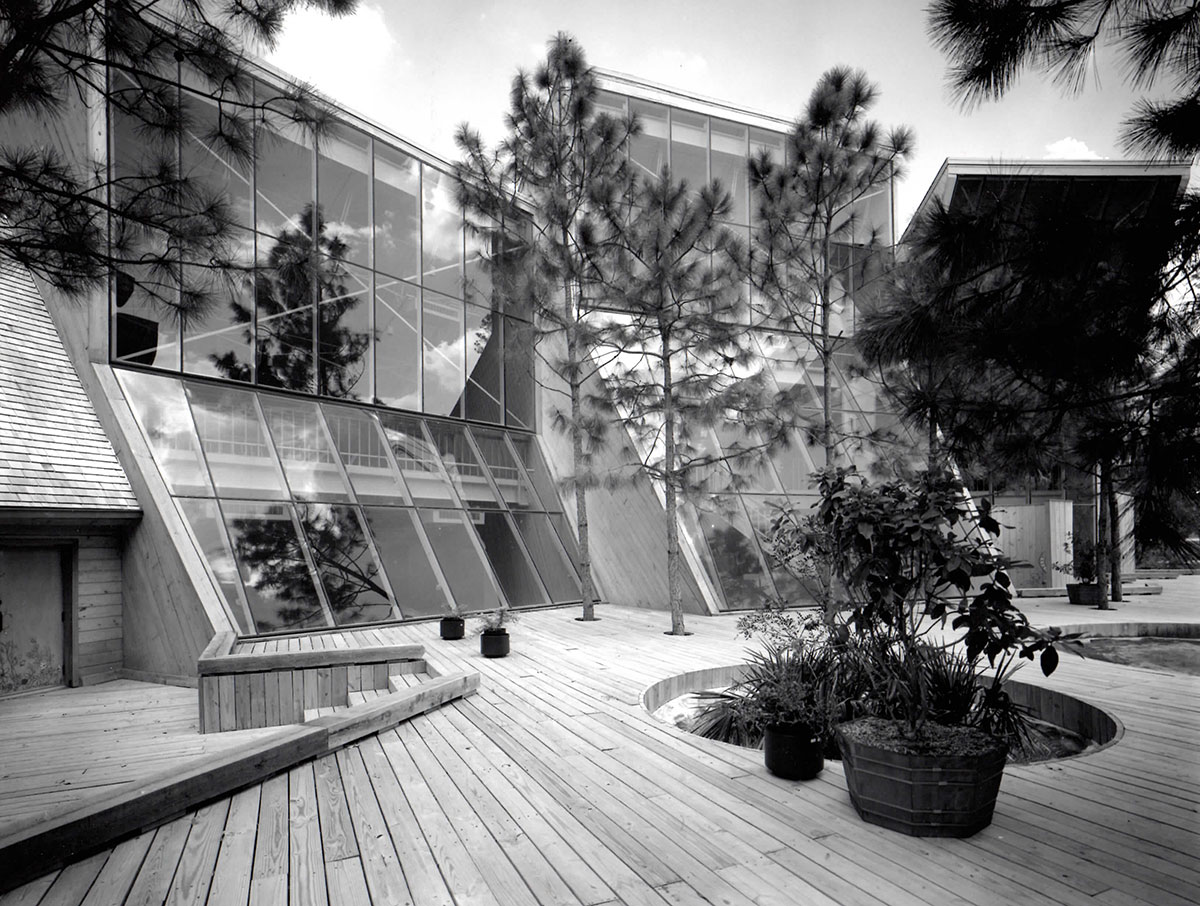

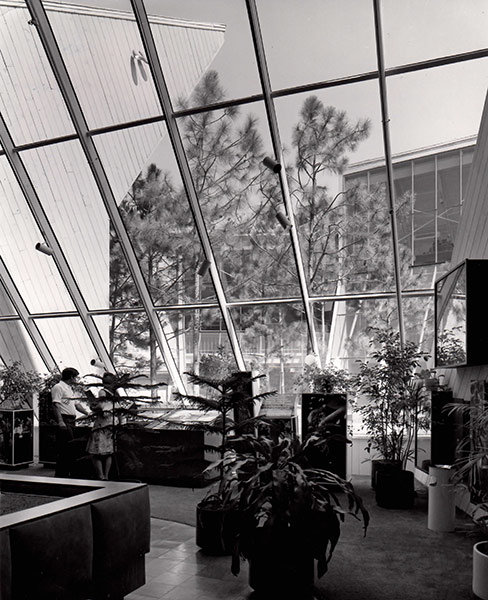

From 1970-2, Bennie's team was responsible for the following large-scale structures: Yavapai Community College, located in the mountains of Prescott in central Arizona; Scottsdale Shadows, a luxury condominium community of 838 units in 13 buildings, near downtown Scottsdale; and the Villa Manana Apartments, a 133-unit complex, in east Phoenix.From 1972-4, Bennie relocated temporarily to Texas where he designed the Woodlands Information Center and Woodlands Inn that were part of a master-planned community on 28,000 acres of land north of Houston. 40 years later, Woodlands has become Texas's top ranked master-planned community with a population of more than 105,000 people. The Information Center received two AIA awards.

Noteworthy 1970s and Early 80s Buildings by Bennie Gonzales

- Camelback Executive Park

- Scottsdale Resort and Conference Center

- Valley National Bank near the Biltmore, Phoenix (now Chase pictured below)

- Cottonwoods Resort and Suites, Scottsdale

- Las Villas, a 55-villa condominium community, Scottsdale

- Hopi Cultural Center on the Second Mesa

- South Mountain Community College, Phoenix

- Master plan, architecture, and landscaping of Palm Desert Civic Center, Palm Desert, California

- Los Sabalos Condominium and Hotel Complex in Mazatlan, Sinaloa Mexico

Transitions

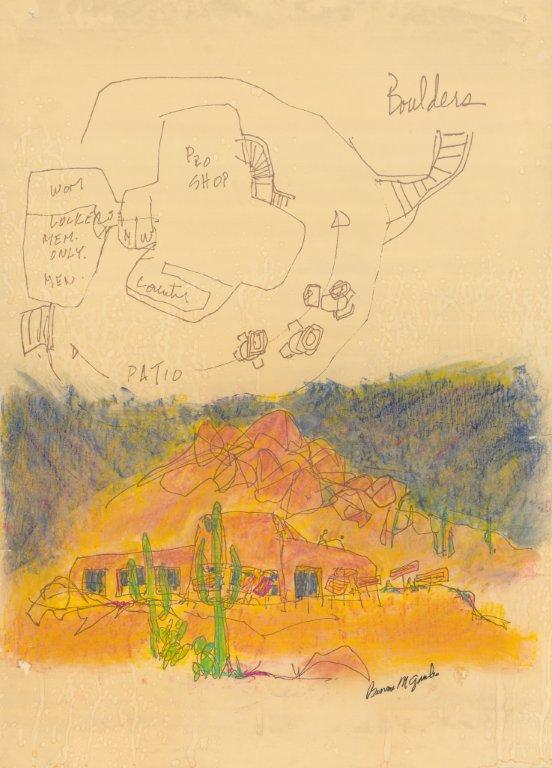

In early 1980, Bennie worked on the Boulders Hotel in Carefree, Arizona. Developers Rusty Lyon, Dick Johnes and Fred Cox were pleased and accepted Bennie's several preliminary sketches and resort site plan. Cox commented that as the "point" man, working closely with Bennie, he was "immediately taken by Bennie's intelligence, energy and charisma."

Source: Fred Cox

Under tremendous financial strain from the breakup of his marriage to Lupe, Bennie had to close his office. This meant terminating the Boulders project that he had worked on for a year and a half. Bennie was so upset that he threw away nearly 30 years worth of work. Fortunately, fellow-architect David Ortega rescued some of the drawings from garbage bins outside Bennie's office.

Trading his Mercedes for a pick-up truck and his suits for jeans, Bennie began the next phase of his life in Mazatlan where he worked on his hotel projects throughout Mexico. He appreciated Mexico's reasonable building codes but lamented on the time it took to bring a project to fruition.

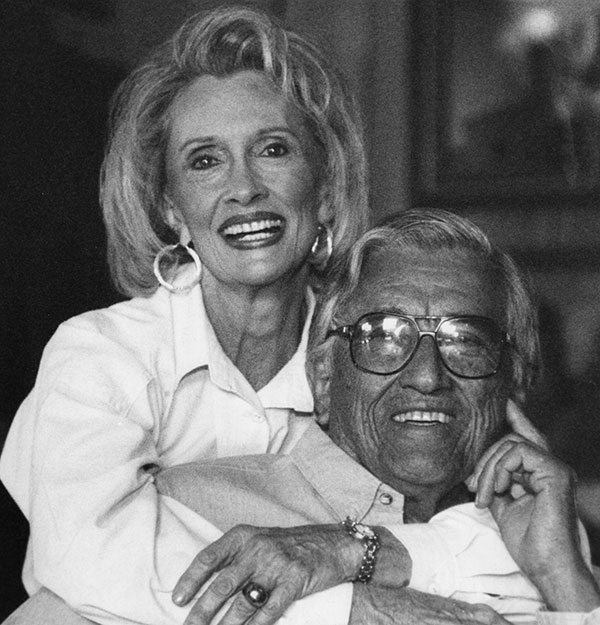

Bennie married Diane Hadley in 1986 at the Los Sabalos Hotel in Mazatlan. Bennie built a house for them in Nogales out of recycled materials, mostly from an old hay barn and a demolished ice warehouse. They furnished it with century-old Mexican furniture and doors. Both painted pictures to hang on their walls. He kept up his practice, designing mostly houses, many of them undocumented.

After a lengthy illness, Bennie M. Gonzales died in 2008 in Nogales at age 84. Architect Vernon Swaback commented upon his legacy, "We have named a street after Frank Lloyd Wright, Paolo Soleri will have his bridge. The city of Scottsdale should figure out a way to honor itself by honoring Bennie." Will Bruder is more concerned with the practical continuation of Bennie's tradition: "Careful consideration of his best work will lead us in many worthy directions as we continue to evolve a real desert architecture for our young, fragile and aspirational community."

Johanna Haver is the author of two books on education: Structured English Immersion (Corwin Press, 2002) and English for the Children (Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2013). She has written more than 75 "My Turn" and community columns for The Arizona Republic, including an editorial on Bennie Gonzales. Three individuals inspired her interest in architecture: her father, Nels Jordahl, who designed and built homes in California; her former father-in-law, the acclaimed Valley architect Ralph Haver; and her husband, retired architect Lloyd Engel.